Devil in The Details

The Post-Shift Naval Treaties Before the Departure (TREATY LORE)

It is January 1, 1922.

The staff of the Memorial Continental Hall have spent the last twelve hours on a collective bender that will change history.

To keep their party going, some of the more adventurous staff procure industrial alcohol laced with various toxic additives as money runs thin and purloined drink runs dry. Eventually, the time comes for them to return to work. They attend to their duties with the grace and dexterity one could expect from those who are extremely drunk—or in the process of dying.

The decorations sag or remain unfinished. The food is badly prepared, with substitute ingredients bought with what little cash is left—everything else having been used to sustain the night’s bucolic buckaroo. Top-shelf alcohol is replaced with libations of questionable nature. Several statues and paintings have disappeared. Every flag in the building is gone, all lost at a game of basement craps.

One item in particular—a bouillabaisse—will be thrust into history. Rotten fish in the dish will officially be the source of the coming cataclysm, though historians will later agree that contaminated alcohol—floor polish in the punch—was the real trigger.

This soiree is not any shin-dig. It is the New Year’s Gala for the Conference on Arms Limitation—known to history as the First Washington Naval Conference.

Bad Fish Soup.

United States Secretary of State Charles Evans Hughes would later recount the events that followed:

I watched as Mr. Tomosaburō gave me the strangest look. He turned red and then green. The color of his face turned positively emerald as he expelled the contents of his stomach into my face. He was very apologetic afterwards, as was I.

Because, of course, my body replied in kind.

It was such a shame, the conversation was quite interesting. I could never muster the courage to broache that topic again after I attempted it once in the fall, at the Second Conference. I recognized the shade on his face and thought it best not to dreg up memories for fear of another geyser. God, the sting in my eyes.

In moments, the Gala turns from a genteel affair into the Swamp of Nurgle. Vomit coats the floor as diplomats and ministers slip and slide. No less than three members of the building's staff will be found dead. The Deputy Head of the French Delegation will crack his head open and nearly die. General Pershing will require hospitalization, along with approximately a third of all delegates and more than half of the staff.

Fingers are immediately pointed in every direction. Agents from every corner of the Federal Government—and the various nations attending—descend on the Memorial Continental Hall. However, no foul play can be ascertained. The primary vectors of malediction were the soup and the punch. The young man who had poured the floor polish into the punch was certain that it was vodka, but he was suffering from acute methanol poisoning and had mistaken the paint can of bootleg vodka for the paint can filled with floor polish. The man who had purchased the fish for the bouillabaisse dies during the day, but the fishmonger who sold him week-old striped bass will attest that he complained about “the others” using too much of the money on booze and that he was clearly intoxicated.

No purpose-made poison is identified, which relaxes tensions considerably. Out of embarrassment and wish to avoid scuppering the arms control talks, the details of the day are left blurry and downplayed. It was merely severe food poisoning caused by spoiled fish bought by a man who drank himself to death.

With most of the senior diplomatic staff of the nine powers incapacitated, the First Washington Naval Conference is closed with negotiations near completion, but still ongoing, for the Five and Nine Power Treaties.

The Nine Powers would reassemble on August 11th, 1922, at the hastily refitted Old Post Office Building.

The Republic Strikes Back

Work on the Nine Power Treaty is rapidly completed and the document is signed just eight days after the Second Washington Naval Conference convenes, most of the work completed in the interregnum.

However, unlike the Nine Power Treaty, there are several simmering crises with the Five Power Treaty—what would generally be known as the Washington Naval Treaty. The terms of the treaty were rather close to completion, and the stances of the powers have now been laid plain on the table.

Critically, work does not completely stop on the Washington Cherry Trees—ships laid down to provide leverage in negotiations or caught in flux—in the interregnum.

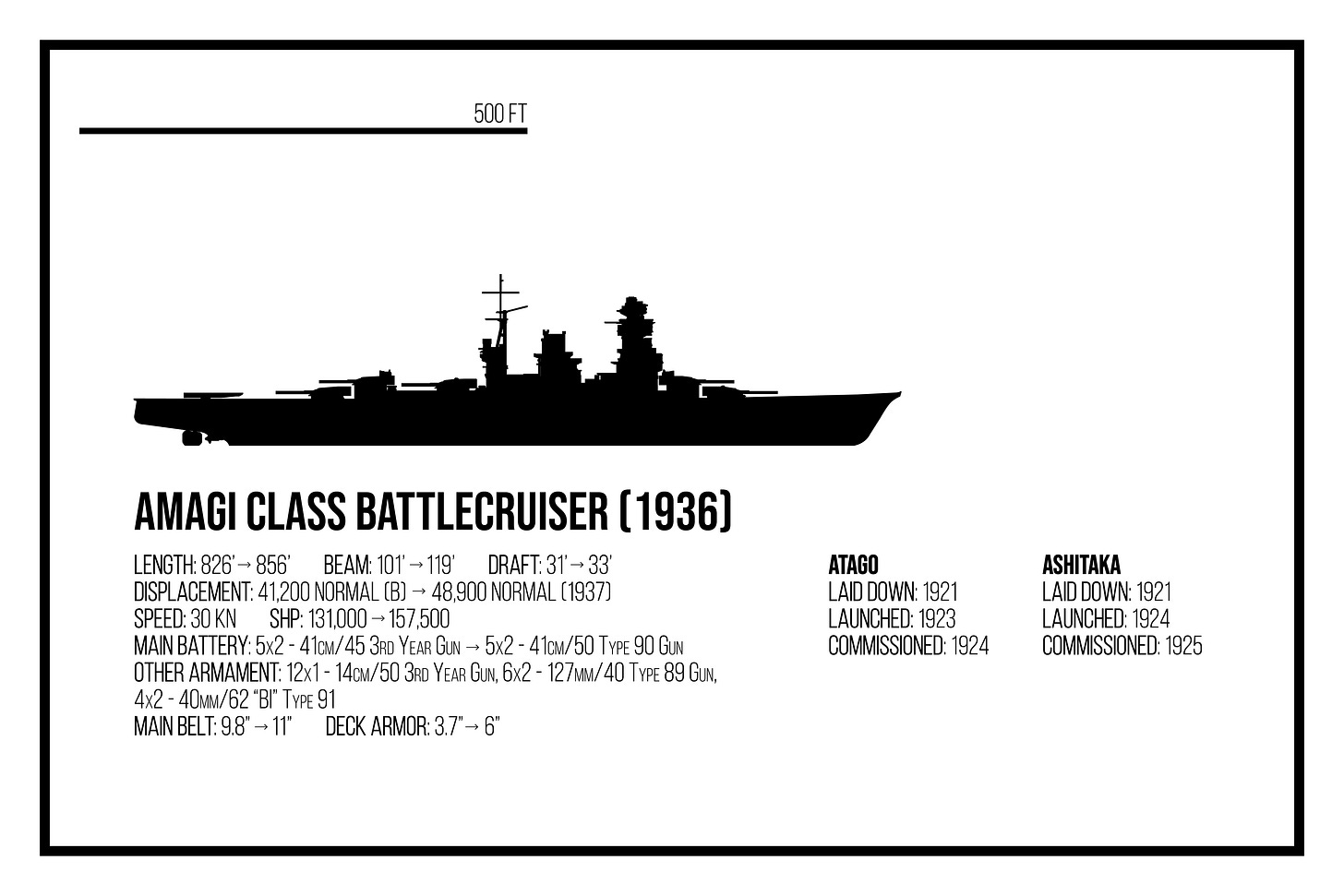

The Japanese battleships Nagato and Mutsu have been working up; their successors, Tosa and Kaga, continue a tepid outfitting process. The Naval General Staff ready the conversion plans for the battlecruisers Amagi and Akagi, and work continues slowly on the latter two Amagi-class, Atago and Ashitaka. The follow-on Kii-class fast battleships are laid down, and work begins, also tepidly. The Battle of the Katōs—between dovish civilian naval minister Katō Tomosaburō and hawkish admiral Katō Kanji—continues to rage, especially after word of the 5/5/3 ratio is leaked.

Similarly, the United States continues outfitting its three uncompleted Colorado-class battleships (Colorado, West Virginia, and Washington—Maryland having commissioned in July of 1921) but does not continue work on the South Dakota-class battleships and Lexington-class battlecruisers, except to prepare Lexington and Saratoga for their fated conversions.

The United Kingdom continues superficial work on the G3-class battlecruisers, laying the keel of four ships (Trafalgar, Agincourt, St. Vincent, Quiberon) and formally ordering four N3-class battleships, but they are not laid down.

The Italians delay their plans to convert the battleship Francesco Carricolo to a carrier pending the new treaty; The French scrap their Normandie-class battleships (save for Béarn, which is saved pending conversion).

Unexpectedly, the United States—who had been the instigator of the conference—goes on one last offensive. First off, they demand that they be able to complete their Colorado-class battleships, then they propose increasing the displacement limit for two carrier conversions up to 40,000 tons, and then they bring up a sore spot left unspoken by the draft treaty at the First Conference: HMS Hood.

Hood displacing 41,200 standard tons is in flagrant violation of the treaty’s limit of 35,000 tons for capital ships. The US demand is simple: if the British get a ship in excess of the treaty limits—they should get one too. They propose a category of “capital vessels for the purpose of trade protection exempt from certain qualitative limitations.” Namely, vessels of this class would be limited to 45,000 tons standard.

The US proposes that the United States and the United Kingdom each be permitted a single ‘Exempter’ vessel. The British refuse. The Americans then argue that if they cannot be compensated for Hood, the battlecruiser should instead be scrapped.

The Japanese delegation is initially horrified by this development, but they then spy that this fight has presented a golden opportunity. They approach the Americans with a bargain: They offer their support for the Exempter classification in exchange for a vessel of their own. The Americans, despite confusion at the offer and concern about underhanded maneuvering, accept.

The British still refuse.

The United States delegation makes a controversial ‘compromise’ offer. Japan would accept the treaty’s ratio of 5/5/3 without reservation, and in exchange, the Big Three—the United States, the United Kingdom, and the Empire of Japan—would be permitted two Exempter ships. The Americans would complete the Colorado class, the Japanese would retain the Nagato class, and the British would be able to construct four 35,000-ton battleships. The nations’ carrier special conversions would be limited to 40,000 tons (at the insistence of the United States).

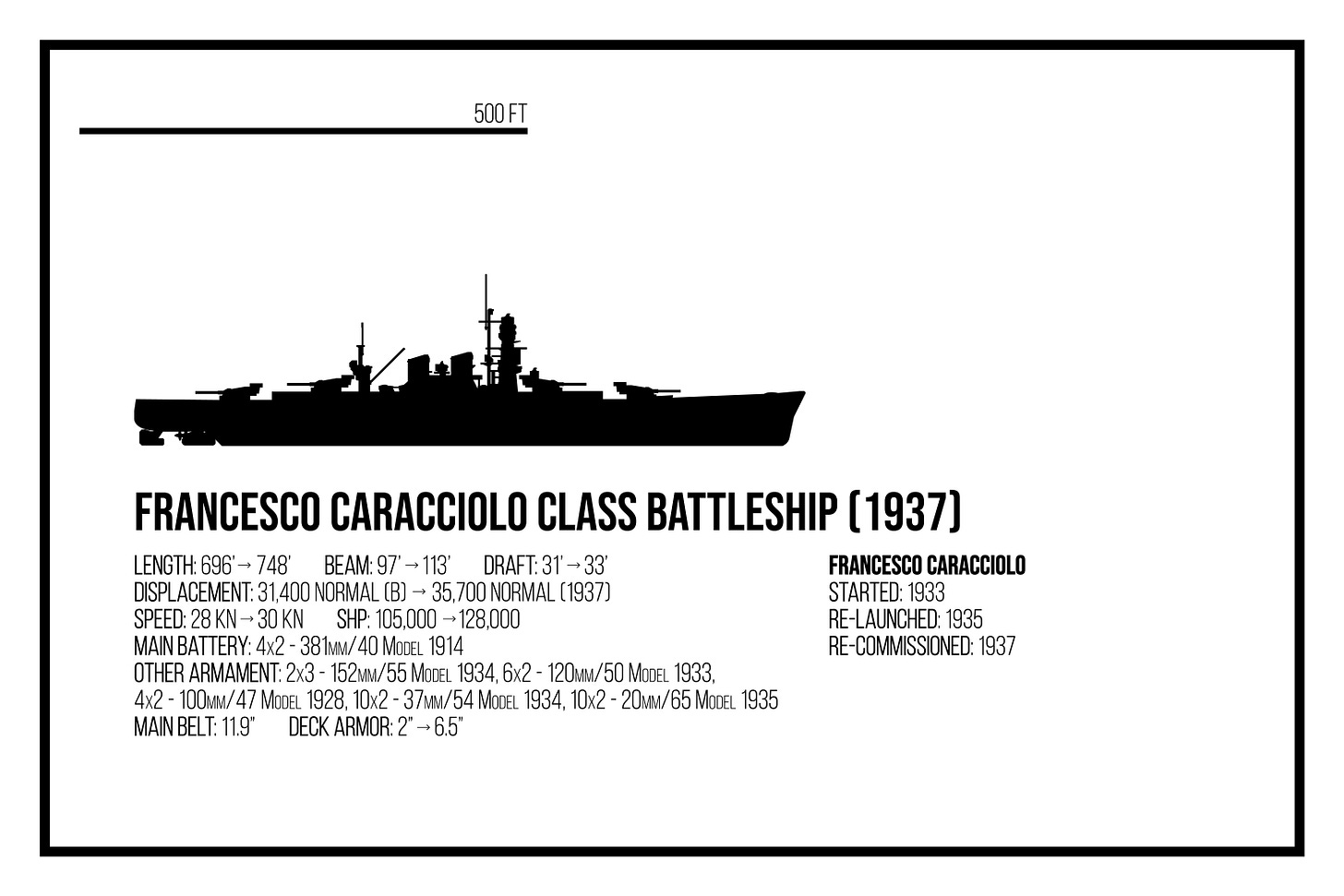

The United States would be able to match Hood and salvage some elements of their 1917 shipbuilding program; the United Kingdom would get a new-build Exempter ship and continue to claim that they had the most powerful ship in the world; and the Empire of Japan would be able to claim parity (in Exempter ships). The increase in total displacement would also permit the Kingdom of Italy to complete Francesco Carricolo as a battleship, in so far as the country had the cash and the willingness to scrap its remaining pre-dreadnought battleships.

No one is happy, but everyone can live with it.

That is, until a coded dispatch from Tokyo arrives at their Embassy in Washington, one that the Cipher Bureau—the Black Chamber—intercepts, decrypts, and translates.

IF NOT POSSIBLE TO COMPLETE TOSA AND KAGA IN A FUNCTIONAL CAPACITY IN ADDITION TO COMPLETION OF EXEMPT BATTLE-CRUISERS HIS MAJESTY HAS INSTRUCTED HIS GOVERNMENT TO WITHDRAW FROM FURTHER NEGOTIATIONS IMMEDIATELY.

The Japanese broach the topic of the completion of Tosa and Kaga—ships that do not qualify as “capital vessels for the purpose of trade protection.” The sudden change of their government’s disposition comes as a shock to their delegates, especially the delegation head, but pressure by militarists in Tokyo—and an offhand comment by legendary Fleet Admiral and genro Tōgō Heihachirōto—allowed a few to seize the opportunity to attempt a change of policy. Tokyo would walk back these instructions—but not only after the chips had fallen.

Washington panics upon intercept of the missive. Their fragile compromise seems poised to collapse. Thus, the Americans hastily convene with the British in one of the most awkward sidebar discussions in diplomatic history. It is a disaster; the British even imply that they would no longer accept an Exempter-less draft and would indeed need a third exempt ship to permit it to at least be a class of two ships instead of a second one-off. The Americans have been hoisted on their own petard—and would now have to live with it.

The final compromise is a horrific kludge that bends the treaty to its very limit. The Americans permit the completion of Tosa and Kaga but as treaty-compliant vessels. The new ships must sacrifice the guns, armor, and machinery to reduce displacement from ~40,000 tons normal to 35,000 tons standard; this proves acceptable to the British and the Japanese delegations. The revision to permit the British and Americans to have three Exempter ships each proves much more controversial, but with revised, dovish instructions from Tokyo, the Japanese sign the deal. In the end, the Japanese end up with a slightly more favorable ratio of capital ships (11:18 instead of 9:15) while still retaining a treaty system to avoid future expenses (what the government was mostly interested in).

The final terms allow for fifteen capital ships of 35,000 tons and three capital ships of 45,000 tons for a total capital tonnage of 660,000 for the United States and the United Kingdom, with 150,000 tons for carriers. Correspondingly, the Japanese would be permitted nine capital ships of 35,000 tons and two Exempters for a total of 405,000 tons and 90,000 tons for carriers. While the French and Italians would be limited to 210,000 for capital warships (six vessels) and 60,000 tons for carriers.

In the end, the United States Navy got what it wanted, and a curled monkey’s paw it had not. However, they do not take this disaster is not taken lying down. The United States Navy will once more embrace one of its time-honored traditions to rectify things—bull-shiting money out of Congress and some creative definitions of what a “refit” is.

Nightmare Keel Rotation

The Japanese are both jubilant and exasperated. While they had gained and then lost parity in Extemper ships and had not reached their minimum desired ratio of 7:10, they have managed to narrow the gap and would enjoy a 7/7/6 ratio in post-Jutland capital ships for the time being. Luck has it that they would have more 16-inch gun-armed ships than the Royal Navy.

With the government not willing to push their luck with the new treaty system, the IJN take Kaga and Tosa back in a reconstruction down to 35,000 tons. This is achieved by removing their fifth turret and barbette, some machinery, and excluding the ship’s fuel and boiler feed, rendering the pair as widly inefficient repeat Nagatos. However, the Japanese government makes sure to carefully store all material removed from the ships… for future purposes.

Ashitaka and Atago are completed to the original Amagi-class specifications without significant alterations, despite Japan having the opportunity to add thousands of tons to reach the 45,000-ton limit for exempt ships. The Japanese government, mindful of allegations of cheating and the cost of reworking partially completed ships, refuses to rework the design—to the annoyance of many in the Imperial Naval General Staff.

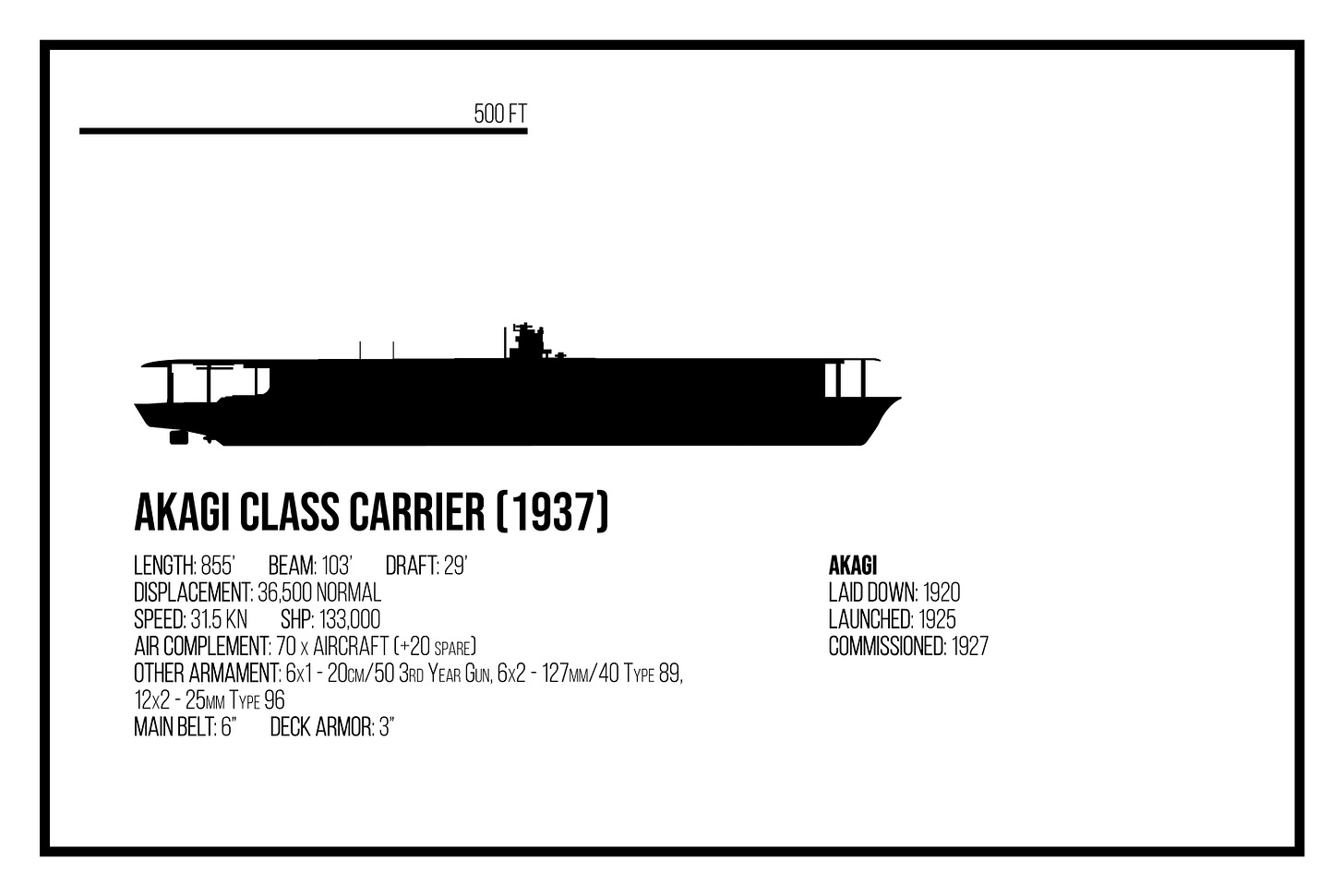

Work continues on converting Amagi and Akagi into carriers. The decision to convert Amagi/Akagi instead of Atago/Ashitaka is controversial. Many argue that it would be better to convert the barely started ships instead of reworking a mostly completed design. However, the Government intervenes—fearful that they would be accused of cheating and mindful of the resources already spent on the conversion process.

Then, of course, disaster strikes. Literally.

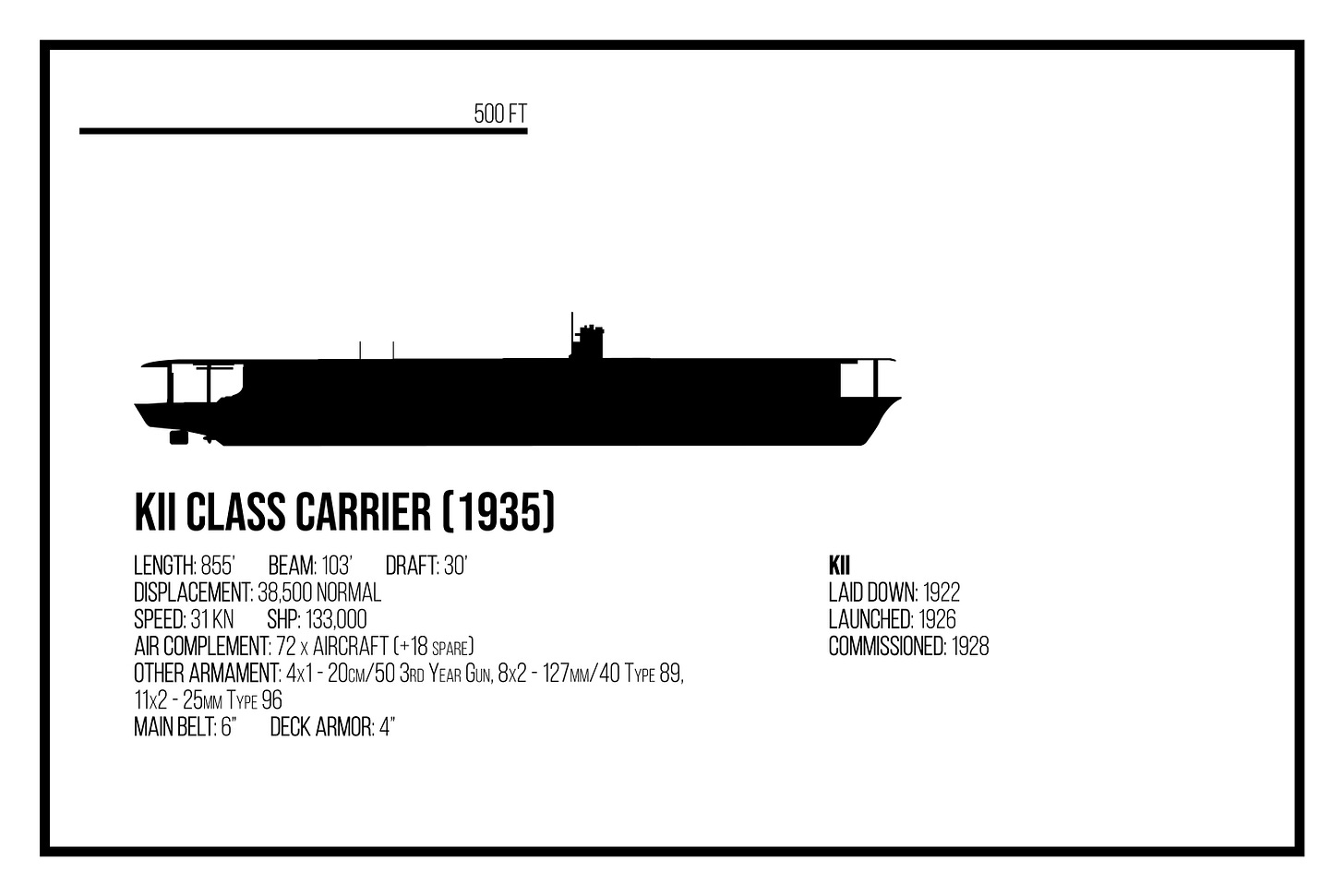

The Great Kanto Earthquake of 1923 devastates Tokyo and the surrounding province, including the Yokosuka Naval Arsenal—wrecking the still-under-construction Amagi and Owari. The ships are wrenched from their keel blocks, warping their hulls beyond hope for repair. Thankfully for the Japanese, the fast battleship Kii—a derivative of the Amagi-class battlecruiser and the sistership to Owari—is still on the slipway in Kure Naval Yard, yet to be scrapped. In fact, Kii and Owari's unnamed sister ships No. 11 and No. 12—would not be scrapped or canceled until August 1924.

The nineteen turrets for Amagi, Akagi, Owari, and Kii would be parceled out, with ten being converted into shore batteries for the Imperial Japanese Army and the rest sent to deep storage.

Heart of a Lion, Face like a Dog’s Breakfast

The British, save for the Treasury, are quite pleased with the terms of the Five Power Treaty. Compared to the other two Big Three powers, their design process is simple and straightforward. There are many iterations, but the risk of the assassination is significantly lower, and requires no enthusiastic interpretations of what constituted a reworking of a design versus a completely new one.

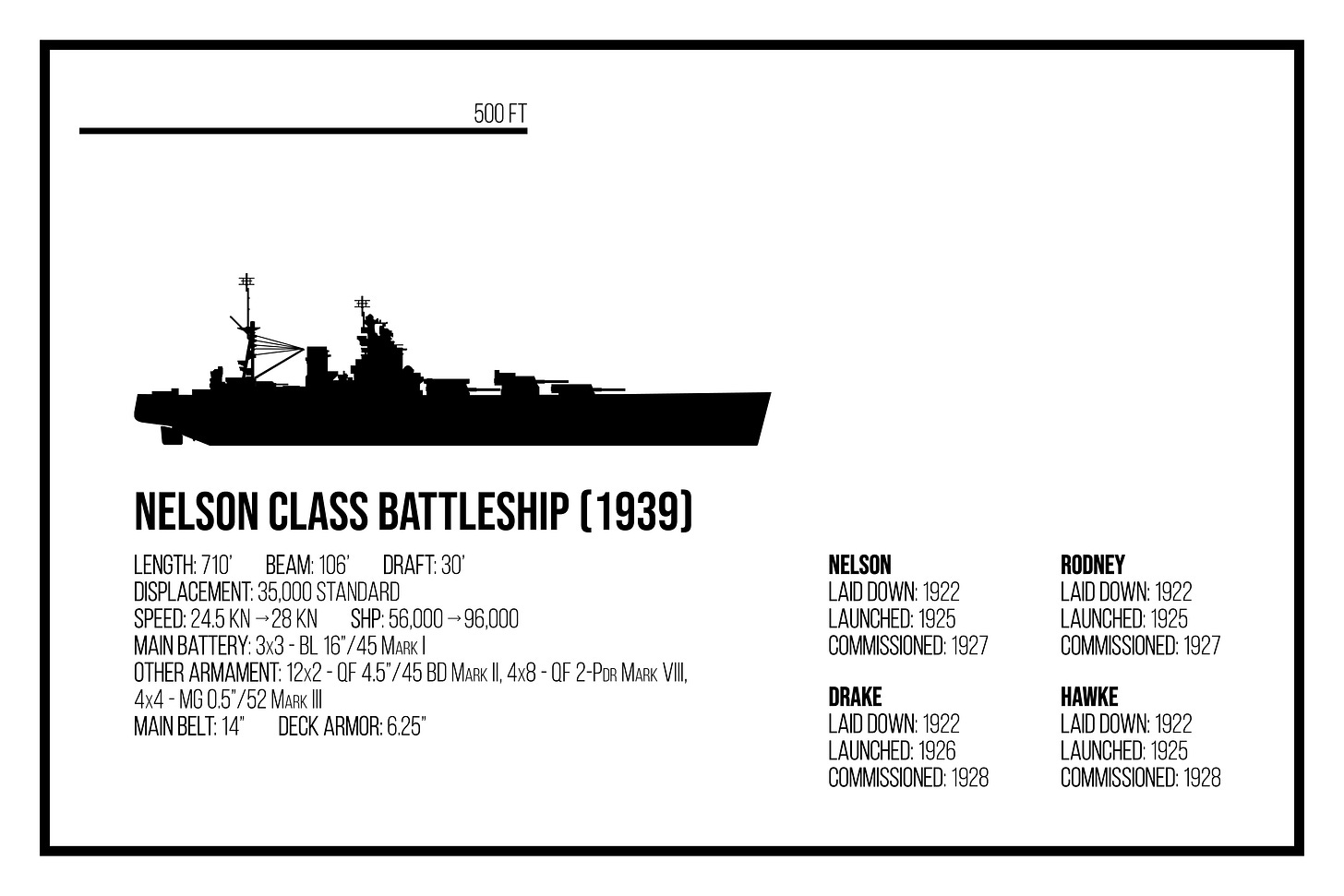

For their four new battleships—Nelson, Rodney, Drake, and Hawke—the Admiralty selects a modified O3 design armed with nine 16-inch guns and displacing exactly 35,000 tons standard.1 The main departure from the O3 design is reworking the six-inch magazines to allow for increased machinery spaces and a design speed of 24.5 knots (functionally closer to 26). The Admiralty had preferred the F3 design, with a speed of 28 knots and armed with triple 15”/50 guns, but felt compelled to build ships armed with 16-inch guns for the sake of prestige—and to maximize their potential fighting power under the new limitations.

The British also decided to convert four carriers from capital ships, with the ex-G3 ships Agincourt and Quiberon selected for the UK’s special conversions, though the final version of these ships will only displace 36,000 tons to save more tonnage for purpose-built carriers in the future. Likewise, Courageous and Glorious are converted to carriers, but since they displace far less than the 30,000-ton limit for carriers, they are counted as “normal” carriers.

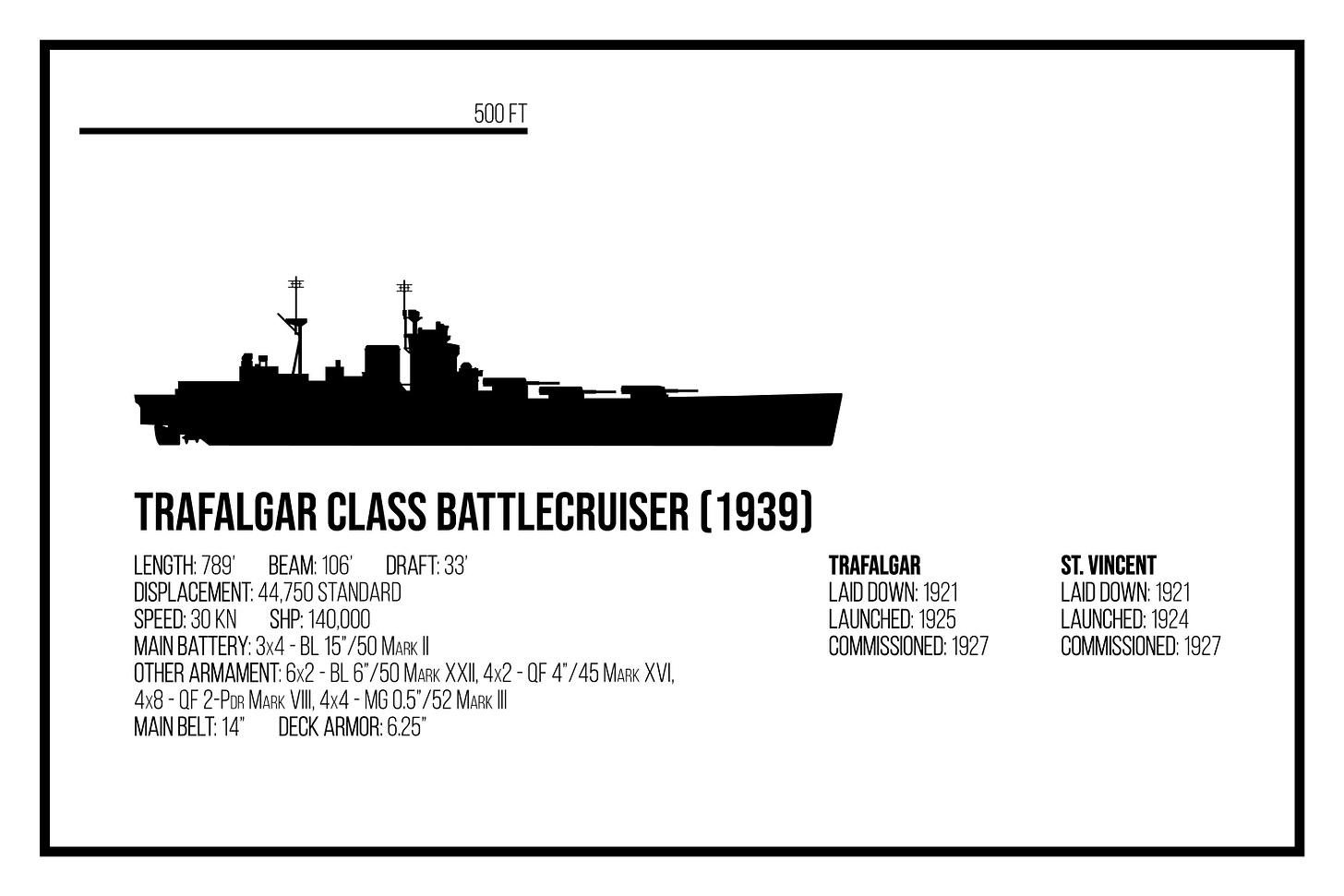

For their two exempt battlecruisers, the British chose to modify the nominally started Trafalgar and St. Vincent. The final design—E4—is, in many ways, merely an enlarged F3 versus a shrunk G3. The ships are 789’ long, displace 44,750 tons standard, and can reach a speed of 30 knots (740’/35,000 tons/28 knots for F3 and 856’/48,000 tons/32 knots for the G3); they are built with protection equal to their Nelson cousins. Their armament—three quadruple fifteen-inch guns in an all-forward arrangement—sets the class apart. These are a new type of gun, the BL 15-inch Gun Mark II with a longer 50-caliber barrel—opposed to the 42-caliber gun on the Mark I guns.

Several factors swing the Admiralty away from either the E3-16 or the E3-15 designs. The E3-15 design was considered not sufficiently armed for their size—not sufficient value for money—and overmatched by the Lexington and Amagi classes. There were also some in the Admiralty who doubted the viability of the new BL 16-inch Mark I gun (which would prove prescient).2 The single most important factor behind the adoption of the radical gun layout was future-proofing. Once they began building BL 15-inch Mark II guns, they could quickly and easily upgrade their forest of Mark I-armed ships with the new gun, increasing the lethality of their battle line without radically altering their weight.

As Admiral David Beatty, the First Sea Lord during the development of the E4 and O3 classes, put it in 1935:

With the Mark II we had a pocket aces in case the edifice of armament reduction came crashing down—as it bloody well has.

With the E4 design, even if the BL 15-inch Mark II was inferior to the likes of the US 16-inch/50-caliber Mark 2, Trafalgar and St. Vincent could simply overwhelm the target with a great volume of fire or escape with greater speed.

Legally, You Have to Say These Are The Same Ships

While the incumbent Japanese Government trembled at the thought of the other treaty powers calling them on their good fortune and the United Kingdom followed the rules of the Treaty to their best possible advantage—the United States Navy would bend the treaty to the very limit out of pure spite. They had been hoisted on their own petard, and they would not let that stand without recompense.

The USN selected three incomplete Lexington-class battlecruisers USS Constitution (CC-5) USS United States (CC-6)—the next most complete ships—and surprisingly, USS Ranger (CC-2), which was far less complete. This is because the General Board did not intend for the ships to completed as designed. In fact, the ships would be effectively new designs, with much work on CC-5 and CC-6 undone and then redone. This would become known to the Japanese as the “Battlecruiser Abuse.” To add insult to injury these “same” ships would be renamed (a second time for CC-4 and CC-5).3

Simply put, the General Board of US Navy, unable to build the squadron of heavily armed scouting ships it wanted, decided to stop kvetching and learn to love the Hood. Thus, the ships were rebuilt to the standard of “Scheme B” for Battle Cruiser 1919 (S-584-135). This design included eight 16”/50 guns, an angled 12-inch main belt, and 33 knots of speed on exactly 45,000 tons standard.

The Navy was only stopped from building three “Scheme D” ships (30 knots with a 12-inch belt and twelve 16”/50 guns on 47,125 tons) for fear of overshooting the maximum allowed displacement. The US was prepared to argue that they merely used the ships refit reserve of 3,000 tons during their construction. However, this would have almost certainly reignited the naval race—and more importantly, Congress had outright rejected the idea of giving half the funds needed for three Scheme D ships.

In fact, the Navy was only able to fund the reconstruction of the three ships—the Big Three—by dipping into other accounts and beseeching Congress for additional funds (which were not forthcoming). This ‘Puritan Program’ (named after USS Puritan (BM-1) ‘repaired’ into a new ship in 1874) nearly killed the Navy’s treaty cruiser build program.

With their extensive modifications and the complications with gathering more funds, Concord, Bunker Hill, and Valley Forge would commission after their elder half-sisters Lexington (CV-2) and Saratoga (CV-3). An aside, the class would technically remain the Lexington-class Battle Cruisers but would functionally be called the Concord-class—as CC-5 was the first ship laid down of the completed batch.

The Italians would scrap their four Regina Elena pre-dreadnought battleships with the dreadnoughts Dante Alighieri and Leonardo da Vinci to provide money and materials to complete the languishing Francesco Carricolo as a battleship. The Marine Nationale attempted to gather funds to complete a capital ship to counter the Carricolo, but those moves would stall almost immediately.

From London to Geneva and Back Again (Twice)

The Washington Treaty signed in October 1923 was obviously not a perfect document, and over the years, loopholes were exposed that required addressing, especially with regard to cruiser submarines, large destroyers, and aircraft carriers displacing less than 10,000 tons standard displacement. There was also much desire, especially in the British camp, to impose further qualitative restrictions to permit the construction of smaller, less expensive warships. The United States did not appreciate the potential budgetary wound that would be inflicted upon themselves if they were actually forced to build up to treaty requirements and wished to limit cruiser tonnage even further, something particularly unacceptable to the British and their global empire.

The first bout would be attempted in Geneva in 1927 and would prove a dismal failure.

Neither the French nor Italians attended; instead, they maintained that the proper venue was a League of Nations general disarmament conference (that conference would begin in Geneva in 1932).

This First Geneva Naval Conference in 1927 would mostly serve as a tourney ground for the United States and the United Kingdom to spar over cruisers with Japan attempting to get the best deal possible. It would end without an agreement.

However, these discussions—followed in 1929 by the inauguration of the new Hoover Administration—eventually led to a compromise on cruisers.

Thus, the Five Powers would assemble in January of 1930 and reach a new agreement. The loopholes would be closed, cruisers would be separated between heavy and light classifications, and the battleship holiday (pause on construction) would be extended for another five years. The powers would also relieve themselves of vessels in excess of the treaty’s numerical caps for (non-exempt) capital ships (15/15/9/6/6). There was an attempt to further reduce the cap on capital ships to 10/10/7/5/5, but this was vetoed by the French and Italians, who then also refused to sign the treaty.

The terms would set off a firestorm in Japan. The IJN was forced to retire two Kongo-class battlecruisers, leaving only Haruna in service; Hiei having been converted to a royal yacht and training ship in 1924 under the Washington Treaty. Extending the battleship holiday, reasonable under the economic conditions, also infuriated the Imperial Naval General Staff, who had just selected designs to replace the Fusō and Kongo classes. Japanese heavy cruiser construction would also have to be curtailed; their large “special type destroyers” were now treaty-limited; their clever plan to skirt requirements with under-10,000-ton carriers was also foiled.

These issues would lead to the resignation of the Chief of the Imperial Naval General Staff, Katō Kanji, over his refusal to attend a state dinner in honor of the American Ambassador to Japan. He would be replaced by Prince Fushimi Hiroyasu, another member of the anti-treaty Fleet Faction.4 In a bid to control the Fleet Faction after the attempted assassination of Prime Minister Hamaguchi, the new Prime Minister Baron Wakatsuki Reijirō appointed moderate, ostensibly liberal Admiral Mineo Ōsumi as the Minister of the Navy in late 1930.5

Baron Wakatsuki’s government, unable to control the Army and prevent the “Mukden Incident” from escalating into an invasion, would resign in late 1931. Prince Saionji Kinmochi, the last genrō and closest advisor to the Emperor, would ask conservative Rikken Seiyūkai leader Inukai Tsuyoshi to form a new government amidst the 1931 polycrisis. Inukai would form a minority government comprised of hostile factions. Despite a mandate from Prince Saionji to avoid drastic changes in policy and locked out of the Diet, the Inukai Government would be a watershed moment for Japan.

He takes Japan off the gold standard, deploys additional IJA forces to Manchuria and Tianjin, and issues a qualified denouncement of the Naval Treaties. Despite written instructions from the Emperor to not acquire to the militarists, Inukai accepts that the Army is out of civilian control and attempts to prevent the Navy from revolting. On the advice of Minister Mineo, the Government would attempt to forestall further radicalization in the Navy by denouncing the treaty system and unilaterally asserting quantitative parity—while also asserting that they would keep to the treaty system’s qualitative limitation.

Critically, the Japanese Government would follow up this declaration with a major expansion program for Japan’s naval industry and shipyards—but not actually fund a shipbuilding program, yet, save for a pair of experimental heavy cruisers, which the Diet was informed was merely like the cruiser Yubari from a decade prior.

Japan’s formal denunciation of the Washington and London Treaties is issued on December 29, 1931, forcing a conference of the contracting powers within the next year.

It seems with Rikken Seiyūkai’s triumph in the February 1932 General Election that Inukai had threaded the needle and overcome the odds. He is shot by radical junior naval officers in his office in May, six months after forming his government.

The horses were now out of the barn, and there would be no going back.

The denunciation of the treaty comes as a shock to Washington and London—and is met with… confusion at the contradictory nature of the move. The Japanese announce that they would leave the treaty—while saying they will still abide by its restrictions?

But the world does not stop.

The British and Americans make bilateral attempts to get the Italians and French to sign the London Treaty—and fail. Wider Anglo-American cooperation is sclerotic—with a single informal conversation between the two notional fellow travelers—with ill feelings from Geneva and the compromises of London at the forefront of both parties’ minds.

With Japan departing the treaty system and several intelligence reports stating that Japan had already funded doubling the displacement of their planned “10,000” ton carriers, the Hoover Administration attempted to re-establish deterrence. They would wave the bloody check. They would bluff that they were willing to bear the expense of starting a naval arms race during a severe recession to intimidate the Japanese back into the system. So, the Navy would get another “super ship.” Like the Concord-class before her, USS Ranger (CV-4) would be reborn on the stocks, turning from an “economical” 14,500-ton small carrier to a 30,000-ton monster. The Japanese would not be cowed so easily; they would make no reply. Ironically, behind the scenes, Ranger would ensure that Soryū and Hiryū would be built as “full” fleet carriers, as the debate had not actually been settled in the Imperial Naval General Staff.

In the Americans’ minds, one calculation stands above the rest: the treaty-mandated conference would begin in December 1932 and would likely last into 1933. If a new administration was elected in the 1932 US Presidential Election, the conference would likely conclude just before it was sworn in March. It would be potentially even worse if the conference continued as the newborn administration would not have been fully confirmed, and the newly elected Congress wouldn’t be required to assemble until December. Despite the concern, the Hoover administration presses on, dispatching Secretary of the Navy Charles Francis Adams III and Chief of Naval Operations Admiral William V. Pratt to London in November ahead of the conference, scheduled to begin on December 3, 1932.

The American hopes that they would find a united front waiting in London would not be realized. Instead, they are blindsided by British demands for a massive increase in qualitative restrictions—reducing individual battleship displacement to 25,000 tons standard and armament down to 12-inch guns. To make matters even worse, the British propose a huge increase in light cruiser tonnage without offsetting the increase with more heavy cruiser tonnage for the Americans.

These proposals land like a sack of potatoes at a blue-blooded wedding.

The Second London Conference lasts two and a half months. The Italians refuse to attend at all. The French delegation leaves in the first week of January. The Japanese delegation pushes strongly for a codification of its unilateral assertion of parity. Naval Minister Mineo hopes to keep the broken treaty system alive just long enough so that Japan can produce a significant qualitative edge with a quantitative draw before the US Congress can act.

The conference finally collapses in February, mainly because the outgoing Hoover Administration is under pressure from Congress—especially Democratic senators who were soon to take control of the chamber and would be needed to ratify a new naval treaty. Roosevelt himself makes it clear to the incumbent Administration that he intends Congress to go into full session in March and not wait until December.

The Second London Conference, much like the First Geneva Conference, ends in failure—primarily because the United States and the United Kingdom are unable to get past their own differences. However, dialogue continues between the two largest naval powers in the interim. Roosevelt himself is deeply invested in naval affairs, interested in keeping the treaty system alive, and is well acquainted with senior USN officers from his time as Assistant Secretary of the Navy during the Wilson Administration. The President sees preserving the treaty system as the best way to forestall an Anglo-Japanese Naval Agreement that would undermine American interests in the Pacific.

Newly minted Chief of Naval Operations William Standley and Secretary of the Navy Claude A. Swanson are directed to Geneva right after being confirmed. They would join the head of the American delegation to the World Disarmament Conference in Geneva, Norman Davis, for further consultation with the British.

The Second Geneva Naval Conference would begin as merely a sidebar to the much larger—and rapidly withering—World Disarmament Conference. It is in these first conversations that the US and the UK are finally able to reach a mutually acceptable compromise. The two great naval powers are on the same page as they bring in the other treaty powers in July 1933. The Japanese join in August and issue their opening bid. They would accept no less than quantitative parity and retroactive codification of their assertion of it, as they had at Second London. The United States and the United Kingdom have no interest in accepting this demand outright. However, the British are interested in some kind of compromise—but the United States, expecting a future conflict with Japan, is unwilling to budge.

The British are primarily interested in qualitative reductions for capital ships and a quantitative expansion of light cruisers. The French are also interested in reductions to capital ship tonnage and maximum guns so that their new Dunkerque-class would not immediately become obsolete. The Japanese also wish for quantitative reductions in “offensive” warships (battleships and carriers).

The United States would break through the chaff and maintain a united front with the British that would effectively dictate the terms of the treaty. This front was forged by consultations between First Sealord Ernle Chatfield by Chief of Naval Operations William Standley. The United States accepts several qualified compromises. They accept some qualitative changes—such as reducing maximum carrier displacement from 30,000 to 23,000 tons—without reservation. Maximum capital ship displacement remains at 35,000 tons, but maximum gun caliber is reduced to 14-inches, and in a key compromise with the British, the US accepts a limit of 8,000 tons and 6-inch guns for new cruiser construction—but acceptance is predicated on a key reservation. These new qualitative restrictions will only go into effect if all Five Powers ratify the treaty.

If any of the other powers refused to sign the new Treaty, the restriction of capital armament would revert back to 16-inch guns after a year. Likewise, if any party refused to sign the treaty, cruiser displacement would be raised back to 10,000 tons standard.

In compensation, the United Kingdom is permitted to retain an additional vessel for trade protection, so long as it is retained by a Commonwealth navy and operated in the Far East until new battleship construction begins. This provision is tailored to allow the Royal Navy to keep HMS Tiger as “a caged cat”—a heavy unit for the Royal Australian Navy. The last of the Splendid Cats was decommissioned in 1931 after the London Treaty was signed but was held off from the breakers after Japan withdrew from the Treaty System.

A final provision permits refits to be comprehensive—allowing changes to guns and armor, instead of limited to just additional protection against underwater and aerial threats and raises the limit of refit tonnage up to 5,000 tons—if any prior signatory (Japan) refuses to sign the new treaty.

The Japanese delegation, led by Rear Admiral Isoroku Yamamoto, makes one last push for a “common upper limit.” It is met with unanimous opposition. Accordingly, the Japanese delegates follow their orders from the Saito Government and withdraw from the conference.

The final elements of the treaty are the Safeguarding Clauses—generally referred to as Escalator Clauses—which would allow the signatories to meet and discuss potential revisions to the treaty to meet changing times.6

The Geneva Naval Treaty would be signed on 17th October 1933—just two days prior to Hitler’s withdrawal from the League of Nations.

Sound and Fury Signifying… Something? Potentially?

The Geneva Treaty—though often lost to the din caused by the German withdrawal from the League—was heralded as a significant success, especially after the dismal showing at London earlier that year. It also allowed the wider Geneva Conference to die a peaceful death with some accomplishment, even if it was much less than what was hoped for when it was begun.

The year 1934 would prove an inflection point.

Rumors continue of a Japanese “super cruiser” in the vein of the “pocket battleships” of the Reichsmarine. The Japanese deny the rumors, and instead claim that the ships are merely treaty-compliant heavy cruises—built in large, covered docks. Estimates by British and American intelligence put the ships at roughly 760-foot length and 60-foot beam, displacing approximately 15,000 tons.

There is the expectation that after these “heavy cruisers” are launched, the United States will call for a Four Power escalator consultation to provide revisions. The US Congress, in expectation of the cruiser escalator clause of the Geneva Treaty, passes the Vinson-Trammell Act (known as the First Vinson Act or the Naval Parity Act), authorizing funds for the US Navy to build up to its treaty-authorized tonnage to match the Royal Navy and keep pace with the Japanese Navy.

The Act would also provide seventy million dollars for the “refit” of USS Concord (CC-5), USS Bunker Hill (CC-6), and USS Valley Forge (CC-4). These refits would be closer to total reconstructions with new machinery and significant increases in deck armor and torpedo protection.

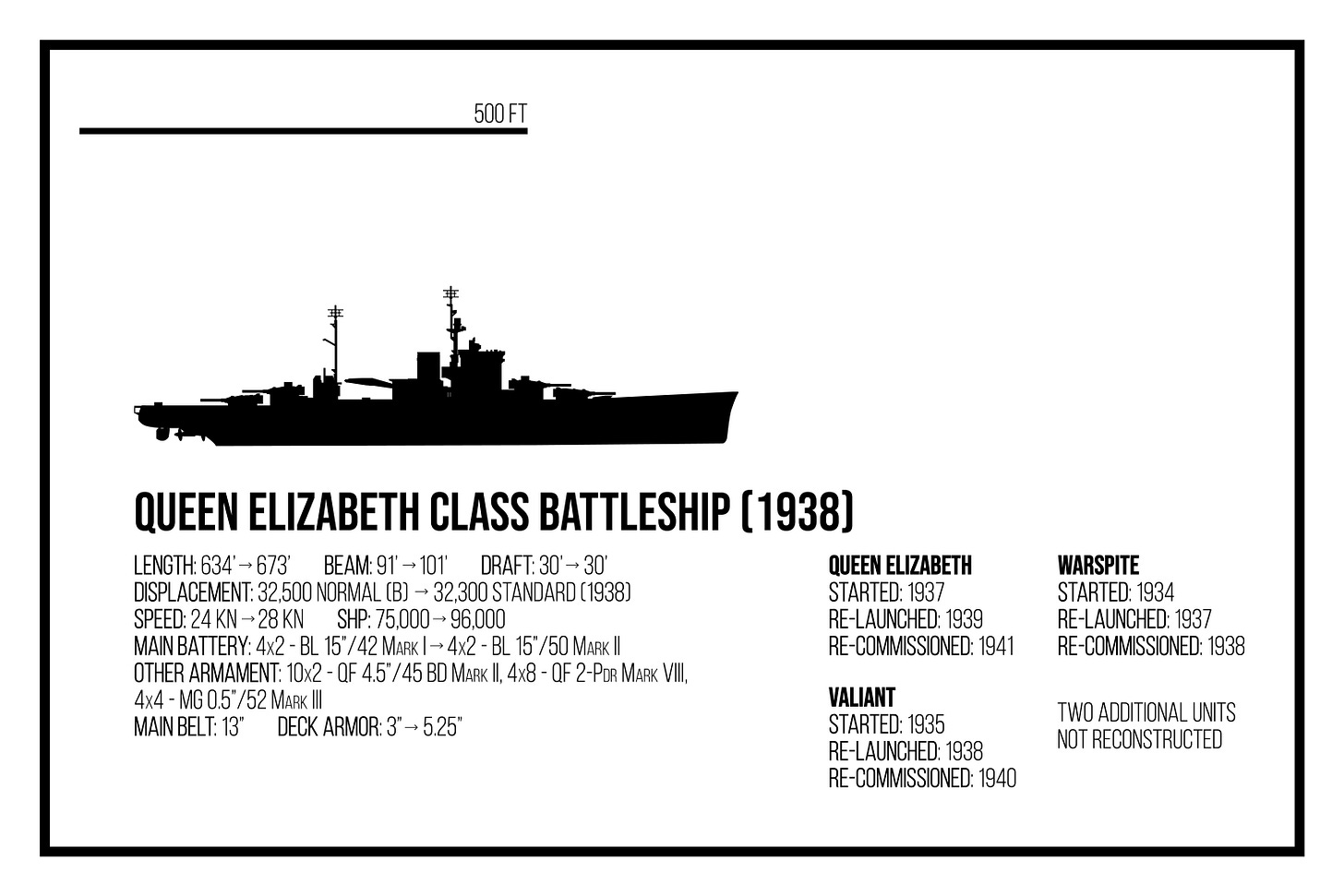

At the same time, the Admiralty in Britain proposes what becomes the “Chatfield Plan” for the modernization of the RN’s battle fleet: a 28-knot standard battle-line and the replacement of BL 15”/42 Mark I guns with the more powerful 15”/50 Mark II. HMS Warspite and the soon-to-be HMAS Tiger are the trial ships. Both ships receive an extended clipper bow and have their power plants replaced, allowing Warspite to reach 28 knots and Tiger to reach 30 knots. The ships also see significant up-armoring and entirely new superstructures. Tiger retains her BL 13.5”/45 Mark V guns with the majority of the United Kingdom’s spare barrels and ammunition gifted to Australia along with the ship herself. Warspite is the first ship to be up-gunned with the BL 15”/50 Mk II guns in new turrets with higher maximum elevation.

The Chatfield Plan is not formally adopted until 1936, but would eventually lead to the reconstruction of HMAS Tiger, HMS Warspite, HMS Queen Elizabeth, HMS Valiant, and HMS Renown. The four Nelson-class battleships receive major refits shy of total reconstruction; they are re-engined to reach 28 knots and fix the lingering issues with their turrets. Further, the United Kingdom would see anti-aircraft conversions and general refits for their older C/D/E-class cruisers.

However, the RN does not have unlimited dry dock space or money, so two Queen Elizabeth-class battleships (Malaya and Barham), both Trafalgar-class battlecruisers (Trafalgar and St. Vincent), HMS Repulse, and HMS Hood are not refitted. The two QEs and Repulse receive new turrets and guns; Hood’s planned “light refit” is put off thrice. The five Revenge-class battleships, scheduled for replacement with the Battleship 1936 class (what becomes the King George Vs), are not refitted at all.

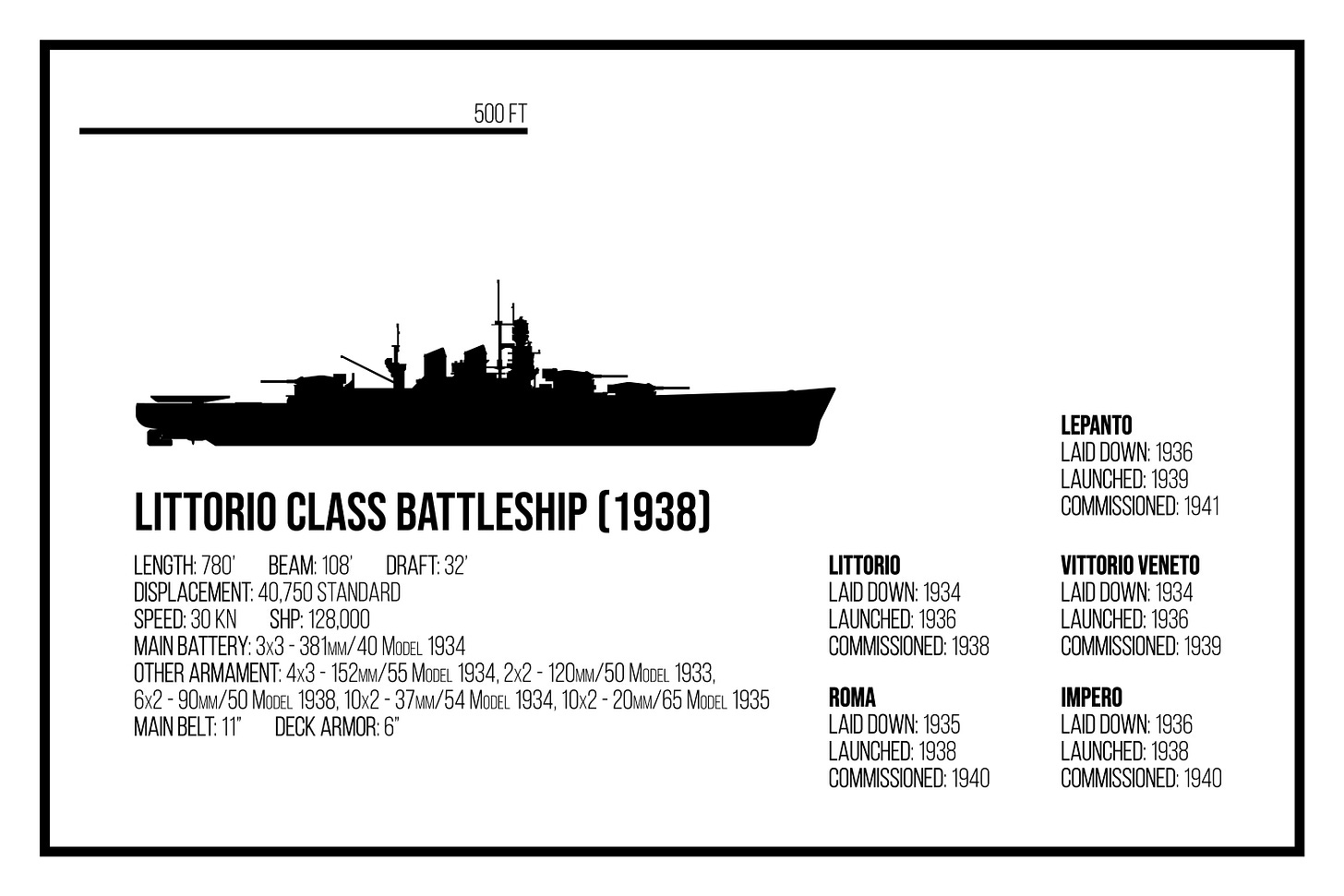

In October, the Italian Regia Marina’s general staff make a fateful decision. There had been a furious debate on how to respond to France’s Dunkerque-class battleships; it is finally agreed that the 15-inch gun-armed battleship Francesco Caracciolo will be reconstructed while the two older Conte di Cavour-class battleships will be scrapped to provide raw materials to accelerate the construction of the new Littorio-class fast battleships. The Littorios will be armed with nine improved versions of the Caracciolo’s 15”/40 guns, though officially, they will be armed with 12-inch guns bored out and relined to 12.6-inch.

Then, on 29th December 1934, Japan unveils its Great Gamble.

Two sleek, long hulls of these “heavy cruisers” are launched on the same day from covered docks. International observers are immediately struck by how massive they appear—well over a hundred feet longer than any other treaty-era heavy cruiser. In fact, after some math, the observing British agent realizes the ships are longer than HMAS Tiger! However, they are certainly not battlecruisers; their beam is too narrow, and their draft is too shallow. In effect, they appear to be upsized Mogami-class light cruisers. Officially, the Japanese admit the ships came in overweight at 12,000 tons standard. When the Director of Naval Construction is informed of the specifications, his reaction is immediate: “NOT BLOODY LIKELY!”

Ikoma and Aso are met with perplexed shock in Washington and London. The ships are clear violations of the qualitative limits of the treaty, and technically, they are capital ships, but they are not so daunting as to make the Treasury or Congress actually terminate the battleship holiday. They are enough to upset the balance but not quite enough to bring the treaty system tumbling down.

It Appears My Superiority Has Led to Some Controversy

Ikoma and Aso are just shy of 760 feet long on a beam of 78 feet, displacing just under 18,000 tons standard. Their main armament is ten 25cm/55 Type 90 guns in five two-gun turrets, though the Type 90 is actually 254cm (10-inch). They are also equipped with eight dual 5”/40 Type 89 secondaries and four triple torpedo tubes and are armored to a cruiser standard with a 150mm angled belt and a 75mm deck. With 10 Kampon boilers producing 191,000 shaft-horsepower, they can reach 37 knots.

In Japanese nomenclature, the new class are Toko-gata Sōkō jun'yōkan or special type, large armored cruisers. They are neither battlecruisers—nor are they either Type A or Type B cruisers (heavy and light treaty cruisers, respectively). They are meant to fill the void between heavy cruisers and Amagi and Tosa-class battlecruisers left by the decommissioning of the Kongo-class battlecruisers. They are to be the apex predators of the IJN’s light forces with long teeth and long legs.

With their speed and sub-capital firepower, they would slash through the American screen at night and land the opening blow on the American battle line with their long-range torpedoes with the fleet’s other light forces to even the odds in the next day’s decisive surface action. Japanese planners estimated they could win the decisive battle if they could bring a force either equal to or at least two-thirds the strength of the Americans, the Special Type Cruisers were there to help ensure that ratio. Outside of the decisive battle, the ships could serve as commerce raiders (this was considered a misallocation of resources and effectively shelved) or to provide an overmatch against the American scouting and screening forces in all venues or conditions, save for an action against a Lexington-class battlecruiser—even then the IJN’s light forces would have the speed to escape if they could not win.

The ships needed armor to resist eight-inch shellfire (6 or 7 inches was considered sufficient) and speed to escape Concord and Bunker Hill (at least 34 knots, as the IJN considered the effective speed of the USN CCs to be 32 knots).

The special type cruiser would serve as a critical intra-fleet factional bargaining piece during the infamous “Whistling Settlement.” This settlement—named for a screaming tea kettle that either went off nine times during the conference or was not touched due to the tension in the air—would see the fruits of the coming naval rearmament meted out between the fleet’s factions. The compromises in the tea parlor that day would produce the contours of the 1934 Naval Armaments Supplement Programme (called the Maru Two or Circle Two Plan): the continued production of special type cruisers, the procurement of an improved 1930 design battleship, the refit of the Tosa-class into fast capital ships, the production of purpose-built fleet carriers, and the production of dedicated light carriers to serve a scouting and screen flattops.

The Carrier Faction would gain two purpose-built fleet carriers—what would become Soryū and Hiryū—and two dedicated scout carriers—Shōhō and Zuihō. These cruiser-carriers would serve as the main scouting platforms for the Combined Fleet, allowing the last two Mogami-class cruisers (Tone and Chikuma) to be completed as dedicated combatants. The fleet carriers Akagi would also be reconstructed with the lessons over the prior half-decade, following the ongoing reconstruction of Kii.

The fleet carrier had been planned to be the 17,500-ton hybrid G8 design with five 15.5cm guns (one twin and one triple). However, Ranger's supersizing and, more importantly, no longer having to keep up the pretense of a 10,000 design would see the two ships upsized to 22,750 tons. Interestingly enough, the chosen design—G9—would conform to treaty standards, save for the fact that it should not have existed at all. The two ships, with the extra displacement, would not suffer from being under-built like most of their contemporary designs, which allowed them to be constructed as an identical pair.

However, the Scouting Carriers—G8-D—would pick up where G8 and its preceding design, G6, had left off. The design was shrunk, permitting greater commonality with ongoing Mogami production. However, the two ships would have severe seakeeping and rigidity issues, which would necessitate a major reconstruction program in 1940, which would convert the mullet battle-carriers into flush deckers.

The Battleship Faction would be quite happy to accept four new battleships into the fold, using Hiraga’s planned Kongo-replacement from 1930 as a baseline to replace the aging Fuso and Ise-class battleships with a single, faster, better armored, and 16-inch gun-armed class. These would become the Sado-class battleships.

The Japanese would violate the battleship holiday but aggressively comply with treaty qualitative restrictions, in hopes of stringing along the Americans and the British. Though a bit slow, the ships were heavily armored and heavily armed—with better armor and more guns than the American treaty-compliant class of battleships. The Imperial General Staff would aim for a standard 26.5 knots for their battleline—the four Sados, the two Nagatos, and the next generation (the nascent super-battleship concept).

At the same, the Amagi-class battlecruisers would come out of their reconstructions, which included installing the new 16.1-inch guns developed for the new Sado-class battleships along with additional armor and torpedo defenses. Kaga and Tosa, which had just been refitted to their original design specifications, would return to the dock dry for total reconstruction—converting the ships into pseudo-Amagis. They would be 74 feet lengthened—a 30-foot stern extension and 44-foot bow extension—re-engined and up-armored. There was a significant kerfuffle over what to call the reconstructed capital ships, with some arguing that the Amagis should be reclassified as battleships while others argued that instead, the Tosas should be reclassified as battlecruisers. Eventually, the latter argument won out as it would delineate the fleet’s fast capital ships organizationally. The end result of this program would be a Japanese battleline divided between four fast (30 knots) and six slow (26.5 knots) heavy units, uniformly armed with a new, more powerful 16.1”/50 caliber gun.

These new battleship units would be financed and resourced, partly through decommissioning the older Kongo, Fuso, and Ise classes and partly due to improving economic conditions. The Fuso and Ise-class battleships would be scrapped outright, providing thousands of tons of materials for the new ships. However, Kongo-class would not be sent to the breakers immediately. Hiei would continue to serve as the Emperor’s yacht, Kirishima as a training vessel, Kongo as a target vessel; Haruna, the final vessel in service, would be decommissioned and stripped for materials. The Imperial General Staff would decide what to do with these aging ships at a later date.

Finally, the Maru 2 plan would authorize the construction of a full class of Special Type Cruisers. These would be modestly larger, with increased armor but less speed. In addition, the ships would have a new turret arrangement, modeled after the Sado-class battleships, with triples super-firing over twins—for the same battery over a comparatively shorter citadel.

The other Treaty Powers were utterly bewildered, especially the Americans and British. The Japanese had broken the battleship holiday—twice! Yet they maintained that they were still following the “spirit” of the treaty system despite the minor fact that the Ikoma-class cruisers were clearly in contravention of the text of the treaties; they were not only beneath the minimum displacement threshold (17,500 tons) set for capital ships under the Geneva Treaty but also obviously violating the 8-inch gun caliber and 10,000-ton displacement limit for cruisers. They were neither fish nor fowl, but certainly… something. The Japanese logic for how this did not violate their commitment to the qualitative limitations of the treaty was not compelling, settling on a national security need to resist American heavy cruisers and following the prescendent of the Deutschland-class panzerschiff. The Sado-class battleships, despite being more dangerous, were less concerning to the Americans and British because at least their construction would cause a temporary reduction in the IJN battlefleet, and they were not a particularly disruptive design, even if it was quite well-balanced, to begin with.

The United States summoned a consultation of the Treaty Powers in March 1935 to discuss the new ships. Neither the Americans nor the British were particularly interested in ending the battleship holiday, especially the British. It was generally agreed that refits could sufficiently counter new Japanese battleship production in so far as they were not particularly disruptive—like the Ikomas. There was much concern that Ikoma would collapse the treaty system. However, none of the other parties had an interest in allowing that eventuality to pass.

The remaining signatories agreed that a new classification of ships, sub-capital “large heavy cruisers,” was justified. The only real point of contestation was upper tonnage: The British wished for a band of 11,000 to 20,000 tons—while the Americans wished for an upper limit of 25,000 tons. Main armament would be limited to 12-inch guns to allow overmatch of the German panzerschiff and Ikoma (and because there was some disagreement over the actual caliber used on the Japanese ships). The French actually wanted an upper limit of 14-inch guns so that their Dunkerque-class battleships could retroactively qualify.

The final agreement was a limit of 20,000 tons, but 25,000 tons if Japan did not agree to abide by the limitations of the treaty. In a final inducement for the Japanese, total “super-cruiser” tonnage would be equal between all parties—two max-displacement ships per nation, a total tonnage of either 40,000 or 50,000 tons standard, depending on Japanese agreement. The Japanese would respond but only to say that they were already following all qualitative restrictions.

In response to the Sado-class, the US Navy would squeeze Congress for additional funding in 1935 for a major refit of the Tennessee-class battleships—following the refits of the Idaho-class battleships and Lexington-class battlecruisers. The refit would be comprehensive and see the ships’ twelve 14”/50 Mark 4 guns replaced with eight 16”/45 Mark 5 guns. Congress was notionally motivated by the Japanese ship program but was mostly interested in avoiding to expense of having to build new battleships to counter it. The would give money for refit but not construction.

The Navy wished its Mighty Nine—the two Tennessee, four Colorado, and three Lexington—to possess a uniform 16-inch main battery. There was even a proposal to refit the Mighty Nine with the new 16”/50 Mark 6 from the refit of the refits of the Big Three (Concord, Bunker Hill, and Valley Forge) that was ordered in 1934, but would prove to be too expensive and was canceled.

Somehow More Perfidious Albion

The British would broach another topic at the Consultation—how the Treaty Powers should engage with Nazi Germany. The British, wishing to bind Germany with an air armament control treaty, saw including Hitler’s Germany in the Washington Treaty System—as opposed to being limited by Versailles—as the first step toward that goal.

The French delegation went apoplectic at the implication that the British had entered negotiations with the Germans to accept their rearmament. They asserted the Treaty Powers should reject the German’s right to rearmament—Hitler’s government having renounced Versailles just days before the start of the Consultation—and that if they were to permit rearmament, it would have to be the result of a general disarmament conference. The Italians also wished for such matters to be settled by a global, general conference. The British wanted half a loaf—and one that covered their own ass. FDR would agree with the British assessment when meeting with their delegates; when he met with the French, he would agree that the British had gone too far; the Roosevelt Administration was deadset on getting the escalator clause invoked—Japan was their overriding concern—not Versailles and Germany.

In session, the Americans would steer the course back to the topics for which the consultation was called. The British would relent and concur that it appeared that the consensus wanted a general disarmament conference. The French would take this as the British had given up the issue.

The Baldwin Government and Nazi German would sign the Anglo-German Naval Agreement in June. Permitting a treaty-compliant German Navy 35% of the strength of the Royal Navy without consulting the French or Italians—and only notifying the Americans before the signing of the treaty. The Germans would only be permitted five treaty capital ships (versus six for the French)—the ratio excluding the Royal Navy’s 45,000-ton exempt ships.

The Germans would also secure British accession for 40,000 tons of additional large cruiser displacement as stipulated by the 1935 Washington Consultation, though this provision was exempt from the escalator clause and would not increase to 50,000 tons.

Livin’ in a Super-Cruiser World

With the 1935 Washington Consultation legalizing a new class of warship, only the Italians would not pursue a large heavy cruiser program. This is because the Italians did not see a need for a cruiser killer when they were already building fast battleships armed with nine 15-inch guns; even something like an Italian 12-inch gun armed anti-Dunkerque would merely siphon resources away from the Littorios. The Italian Navy would briefly reverse course in 1937 after realizing the danger posed by the Royal Hellenic Navy’s large cruiser program, but no design would be selected, and no work would be started.

The Americans would pursue a maximalist design—25,000 tons and 12-inch guns. The finalists were a six-gun (three twins) and a seven-gun design (two twins forward, one triple aft). The General Board would select the six-gun design, as it could have better armor protection and additional anti-air weapons, positioning the ships to be cruiser hunters and natural carrier escorts.

The sisters would be named Ticonderoga and Shiloh. House Naval Affairs Committee Chairman Carl Vinson attempted to veto the latter name but was rebuffed. The pair would be beleaguered by vibration issues their entire service careers due to the new skeg design used in the correction.7 However, the tribulations with Ticonderoga would ensure that the succeeding North Carolina, South Dakota, and Iowa-class battleships would avoid similar pitfalls.

While the US pursued a maximalist design, the British and French admiralties would try to aim for 16,000-ton designs—large, heavy cruisers instead of baby battlecruisers.

Well, the Royal Navy would originally aim for a 12,500-ton design—a modified County-class—to squeeze four vessels out of their allotted 50,000 tons. This would be rebuffed by the Treasury. The Admiralty would try again with three 16,000-ton ships, arguing that it would be less than the approximately £11 million cost of four smaller cruisers. The Treasury—fuming that the Government had supported the Chatfield Plan with money and not just words—would reject this second proposal. Finally, the Admiralty would propose a maximalist design that the Government would force the Treasury to pay for. This would actually end up being the most expensive option.

The Admiralty would get two ugly ducklings. They would displace not much less than a Repulse-class battlecruiser with better armor armor. However, unlike the Americans, the Royal Navy would not adopt a 12-inch gun and instead arm the ships with sixteen new extremely long BL 8”/60 Mk IX guns in four quad-turrets equipped to handle extra heavy armor-piercing shells. The ships would be able to manage 32 knots with battleship protection and enough guns to drown an enemy raider in shells. In short, the two ships, Defence and Black Prince, were built to hunt Pocket Battleships.

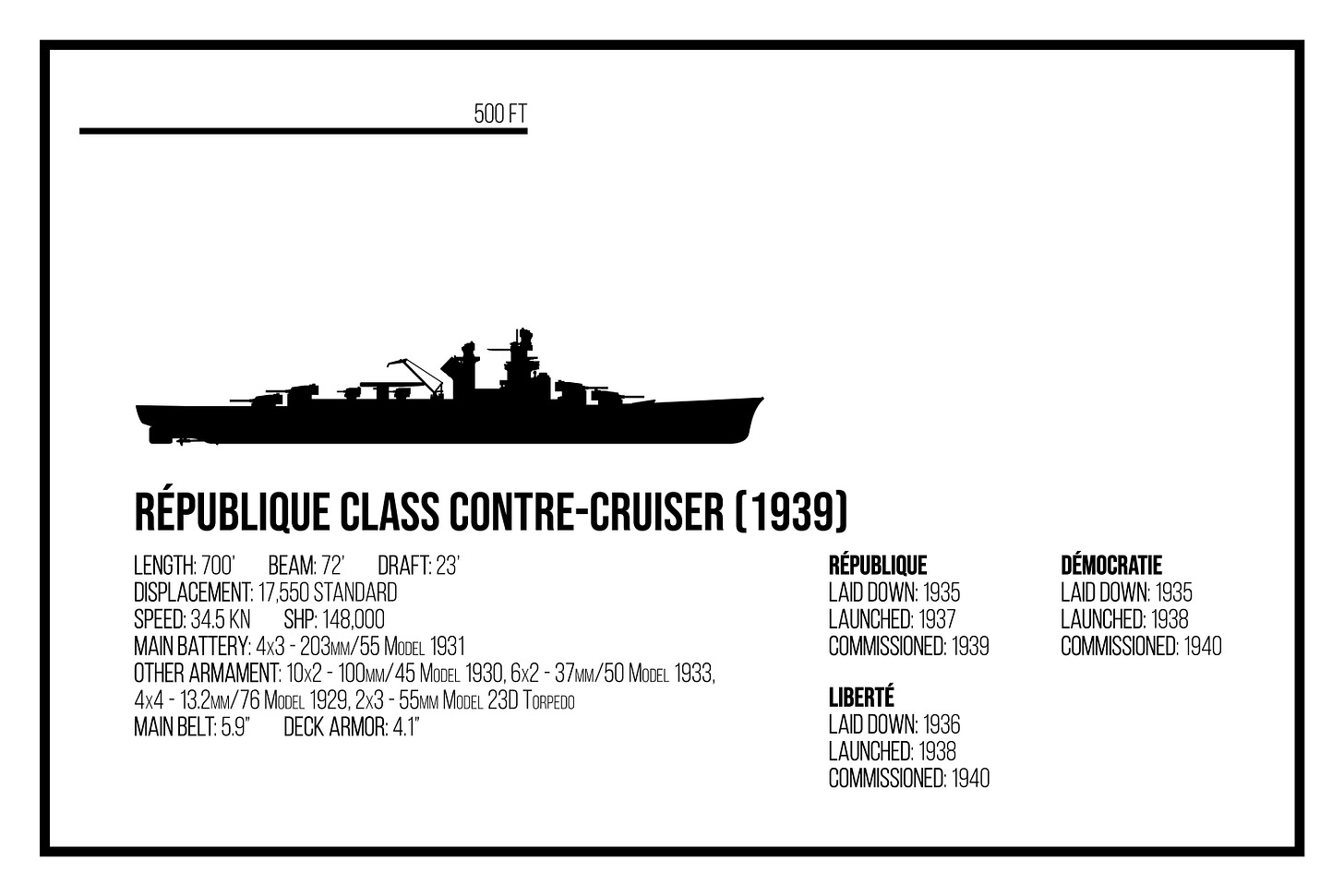

The French would settle on a 16,600-ton design—an enlarged Algerie with moderately improved armored and four triple (instead of twin) 8-inch gun turrets. The ships would begin work in 1936. The first two ships, République and Démocratie, would be completed before the start of the Second World War. République would be interned in Alexandria, while Démocratie would be seized by the Free French in Dakar along with the battleship Richelieu. The last ship, Liberté, would be near completion, outfitting in Brest during the Fall of France, and would make its way to internment in Toulon.

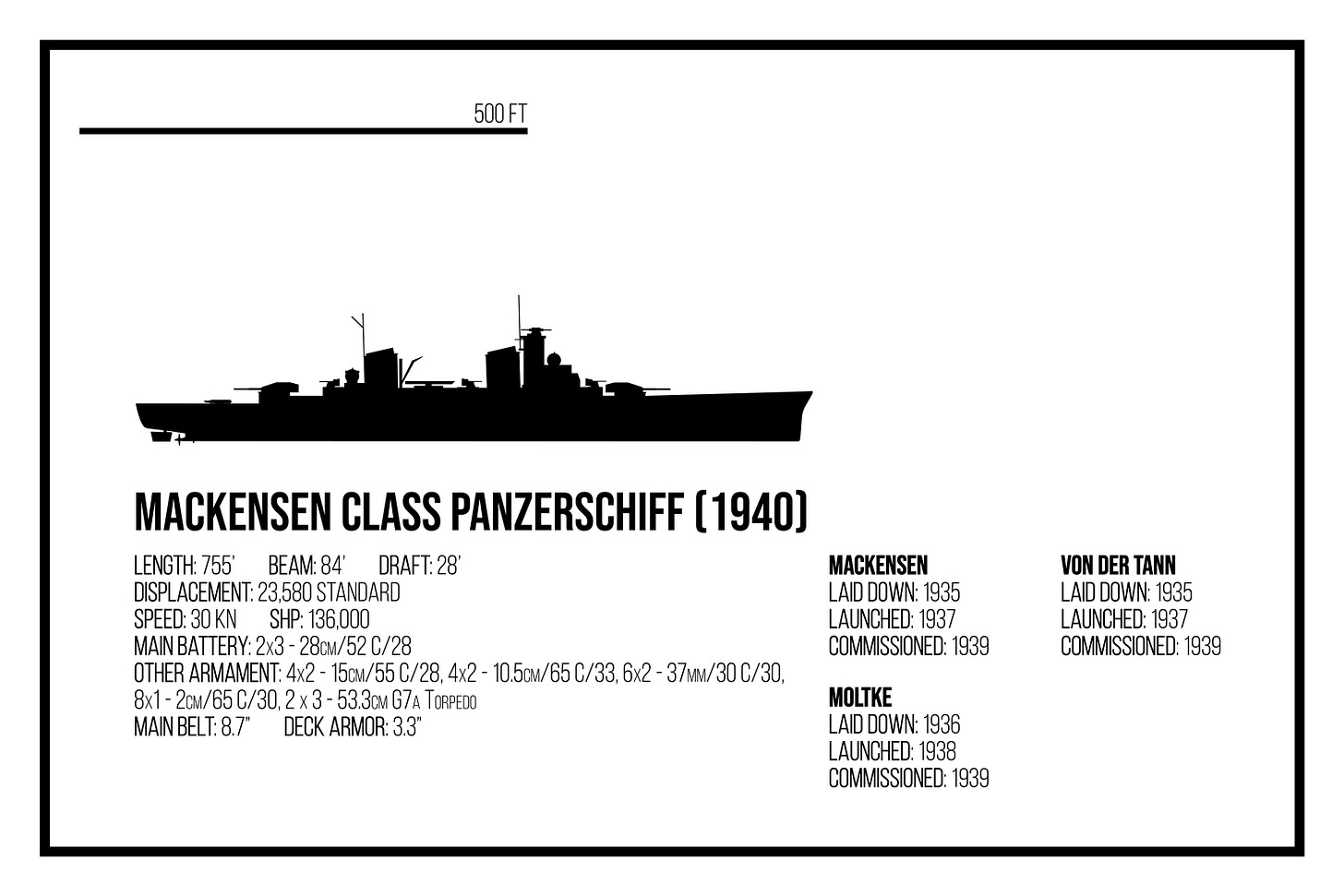

The Germans would eventually settle on a revision of the D-class panzerschiff that had begun work in 1934 before being canceled in favor of Scharnhorst and Gneisenau. Officially, the ships would displace 13,300 tons standard, ostensibly a modest revision on the Deutschland-class panzerschiff so that the Kriegsmarine could procure three under the terms of the Anglo-German Naval Agreement. The class—Mackensen, Von Der Tann, Moltke—would actually displace 23,580 tons standard.

There would be one last participant in the super cruiser race: the Greeks.

Sweating over the expansion of the Regia Marina and fearing the imminent start of Italian super-cruiser construction, the Royal Hellenic Navy would go shopping in Britain in 1936 for a prophylactic against the Italians’ existing and potential cruiser forces. The Director of Naval Construction would eventually settle on an 18,850-ton large cruiser using Vickers’ new 10-inch main gun. The Greeks would buy four; this would cause the Italians to actually consider procuring super-cruisers, but limited naval capacity and funds would scupper those plans after a brief moment of panic.

The first two ships, Salamis and Marathon, were outfitting in Alexandria in 1941 when Nazi Germany invaded Greece. The pair would be “donated” to the Royal Navy shortly after the British had seized them. In any case, there weren’t enough Greek sailors to crew them; before the Italian invasion of Greece had interrupted things, only the first elements of Marathon’s complement had arrived in Egypt. This cadre would be mixed into a scratch crew scrapped from any place where they could be scrounged. The two ships were commissioned as HMS Theseus and HMS Orpheus. The pair were thrown into action immediately. Orpheus would be sunk a month after commissioning during the Evacuation of Crete. The ship was badly damaged by multiple bomb hits before being torpedoed by an Italian submarine as she limped her way back to Alex. The other two ships, HMS Atalanta (ex-Plataea) and HMS Hercules (ex-Gerontas) would be completed in the United Kingdom and be manned by the repurposed crews of the old heavy cruisers HMS Hawkins and HMS Frobisher.

So An Italian and A Dutchman Walk Into a Bar

One nation absolutely terrified by the launch of Ikoma and Aso was the Kingdom of the Netherlands. The swift, large cruisers were seen as a particular threat to the light naval forces defending their colonies. The arrival of super-cruisers incited enough public outcry to force the government to take a significant increase in naval forces seriously. However, the Dutch did not have the infrastructure or industrial base to build capital ships.

So they went shopping, and they ended up at Italy’s doorstep.

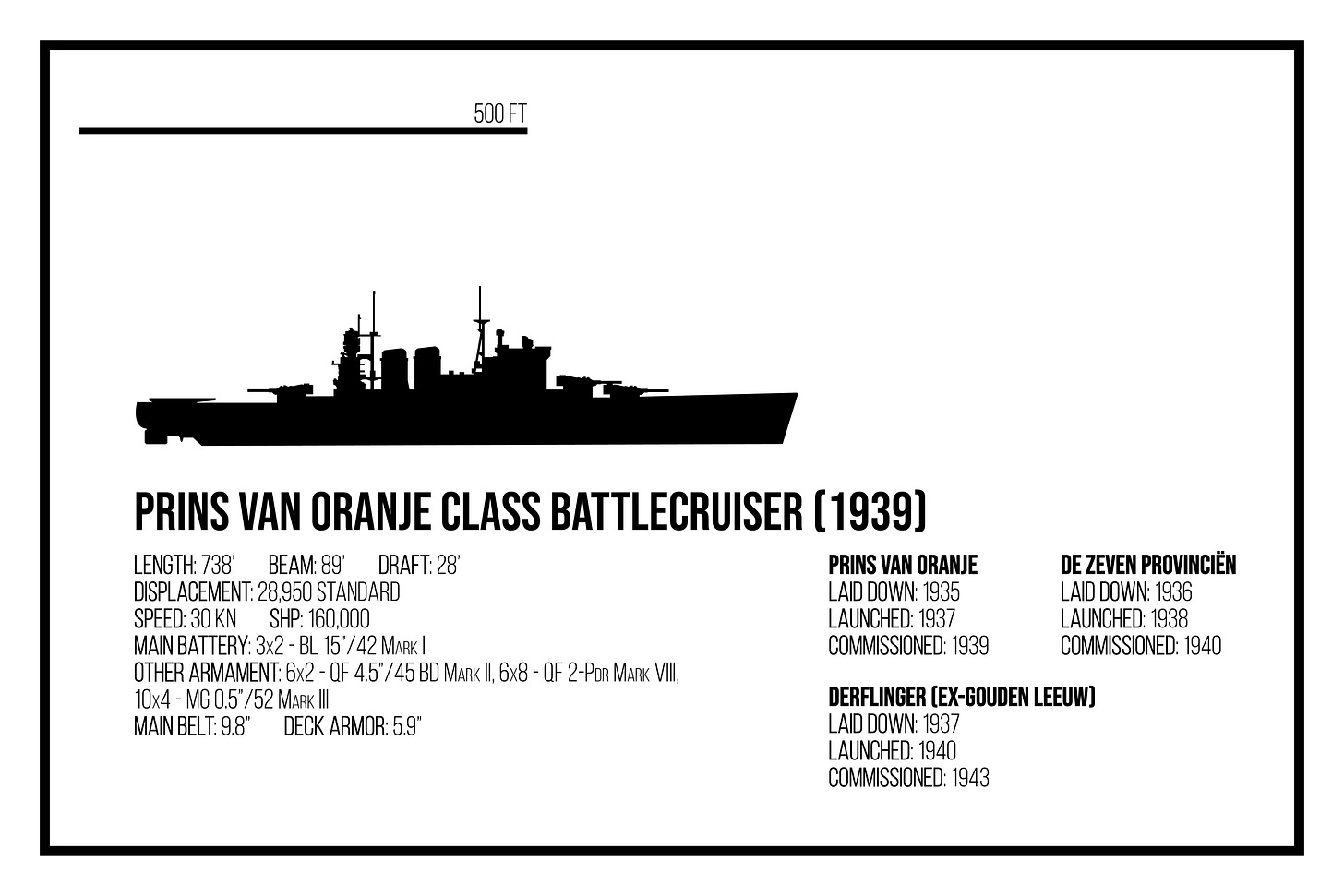

They would go to Ansaldo and ask for a 25,000-ton ship with 12-inch guns. Ansaldo and the Italian Government would be more than happy to comply, using a modified version of the 1928 battlecruiser design. The Dutch and Italian Governments would sign a contract for three ships in 1935 for 250 Million Dutch Gilders (2 billion Italian Lira)—ƒ75 million per hull and ƒ25 million for infrastructure. The first hull would be built in Italy. The succeeding ships would be built in the Netherlands. However, 75% of the material and fittings would be sourced from the Italians, including all weapons, machinery, and armor.

The final design would be 26,500 tons, with twelve 12-inch guns in four triple turrets and eight twin 120mm guns as dual-purpose secondaries. They would have a 10-inch belt, a 4-inch deck, and be capable of 30 knots. The trio would be named Prins van Oranje, De Zeven Provinciën, and Gouden Leeuw.

The program started out controversial and only became more controversial as the Abyssian Crisis became the Second Italo-Ethiopian War. The contract provided a vast sum of material and foreign currency to the Fascist Regime—infuriating the British and embarrassing the Dutch.

In 1937, the Dutch Government succumbed to international pressure and canceled the contract after the launch of Prins van Oranje and the keel laying of De Zeven Provinciën at Rotterdamsche Droogdok Maatschappij. The Dutch would then sign a new deal with Vickers-Armstrong to complete the ships. The ships would be built in Rotterdam and outfitted in Newcastle. The British could not offer a 12-inch gun on a reasonable schedule but could offer older BL 15”/42 Mk I guns and turrets that were surplus to requirements due to the ongoing Chatfield Plan refits.

The ships would have a distinctive profile, as the Italians had already delivered all three conning towers to Rotterdam. The British didn’t believe such heavy structures were necessary but the Dutch insisted; thus, the ships would have a Littorio-style armored conning tower and a Queen Anne’s Mansion-style superstructure.

Prins van Oranje would be completed in 1939. De Zeven Provinciën would be outfitting in Newcastle, and Gouden Leeuw would be nearing her launch when Germany invaded the Netherlands. Prins van Oranje would be lost with Force Z while De Zeven Provinciën would be lost at the Battle of the Java Sea. Gouden Leeuw would be launched by the Germans under the name Derflinger, joining the latter half of Operation CERBERUS, being completed in 1943 with German weapons and equipment.

Despite the contract being canceled, the Italians would gain roughly 1 billion Lira in foreign currency and an additional billion Lira in materiel purchased by Dutch cut-outs (the Italians had purchased more material than needed to circumvent sanctions). This was equivalent to roughly three Littorio-class battleships. In fact, the program would fund the fifth ship of the class—Lepanto. The Dutch currency, paired with the sequential scrapping of the outdated Conte di Cavour and Andrea Doria classes, would allow the Italians to complete their new build battleships in an orderly fashion.

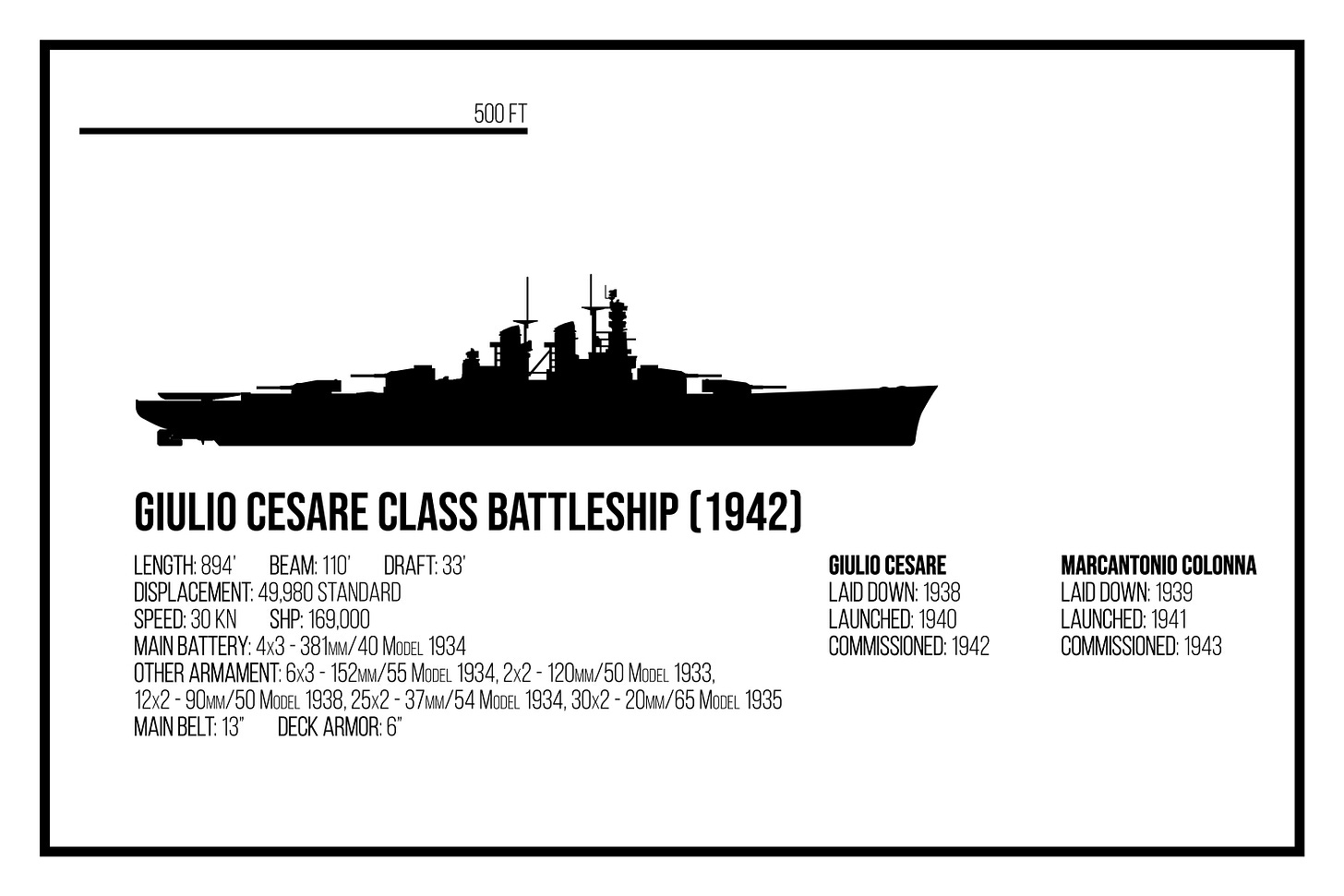

The Italo-Dutch contract would also provide the seed money for the Regia Marina’s follow-on class of battleships—and also a thirty-year legal case about restitution for defrauding the Dutch. More or less, these follow-on ships would be stretched and improved Littorios armed with twelve guns in four turrets. The Regia Marina wished for four ships but would only ever order two—Giulio Cesare and Marcantonio Colonna. The ships would stress Italian naval infrastructure and prove to be less maneuverable than hoped, earning them the nicknames “Porco Giulio” and “Ma Dona Colonna.”

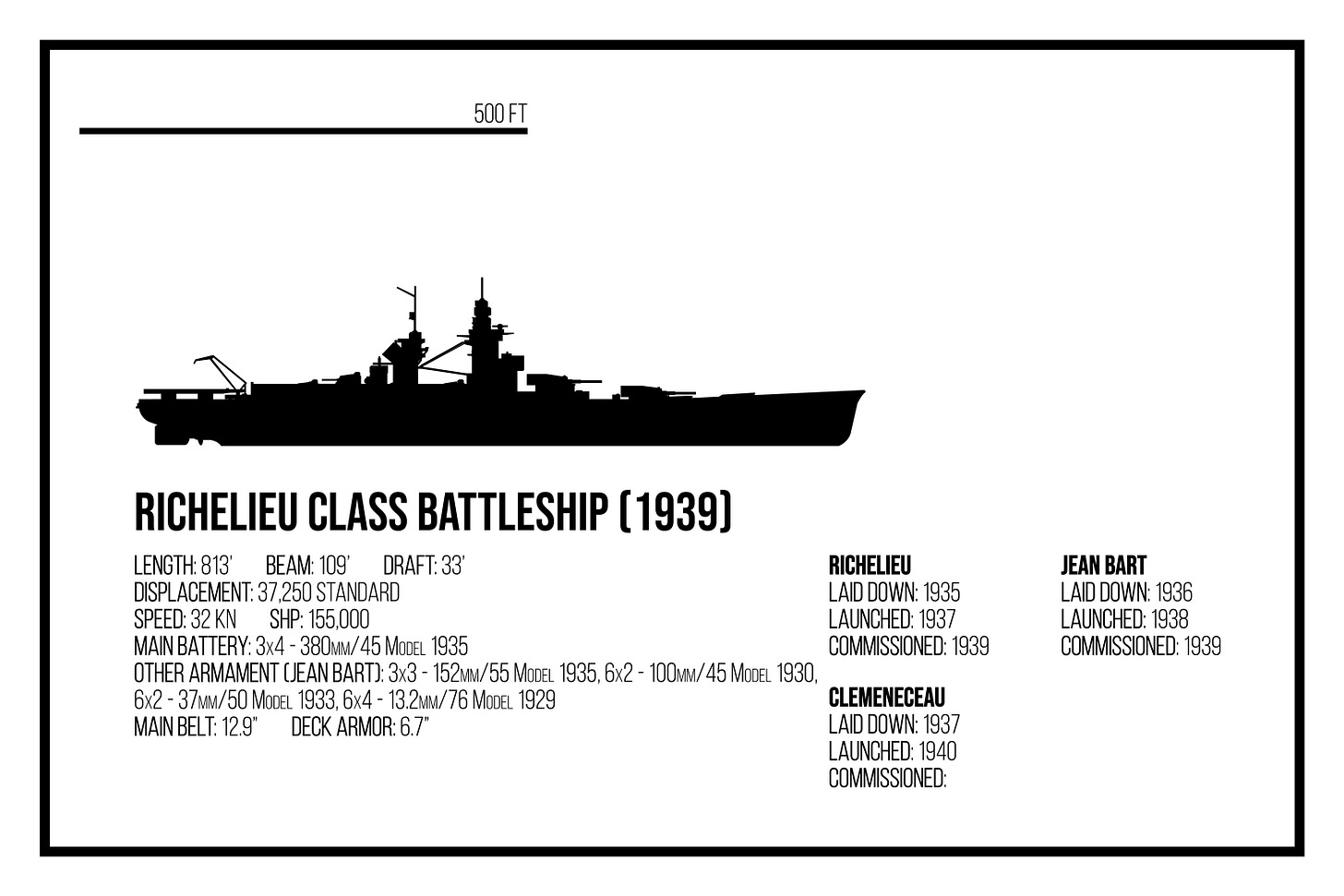

In response to the accelerated construction of Italian capital ships, the French would attempt to match with their own construction of Richelieu-class battleships. However, the capacity of French docks was simply unable to cope with the demand. Thus, the French were only able to complete two ships—Richelieu and Jean Bart before the end of the war. Clemenceau would be hastily readied and launched amid the Fall of France, escaping to Casablanca, where it would duel with the third South Dakota-class sister, Massachusetts, in October 1942.

It’s Less Treaty Cheating and More Treaty Cuckolding

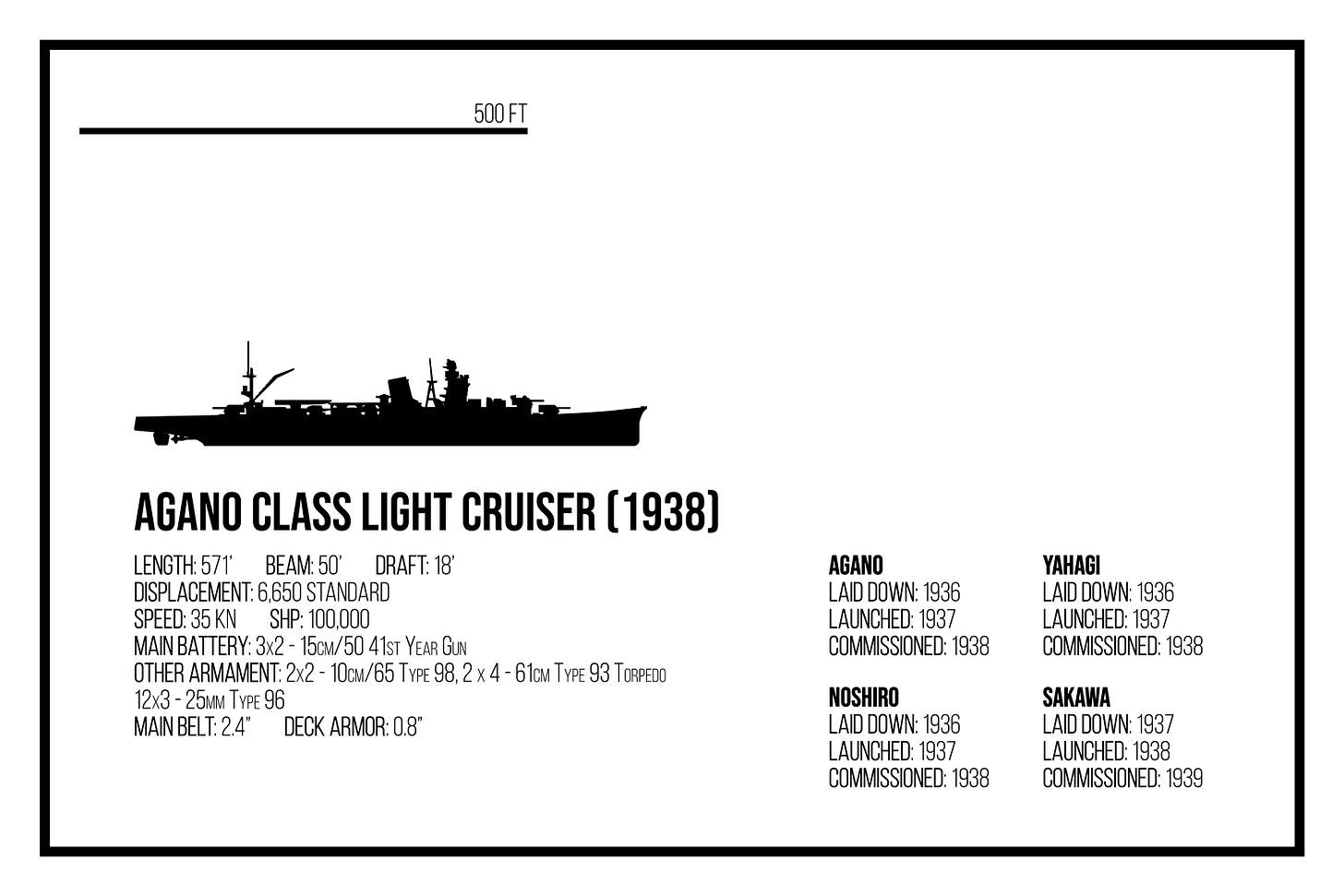

The Imperial Diet would ratify the 3rd Naval Armament Supplement Programme in 1936, which would fund a massive expansion of the Imperial Navy: two Shōkaku-class fleet carriers, two Yamato-class battleships, two Tsurugi-class special type cruisers, four Agano-class light cruisers, and the conversion of the mothballed Kongo-class battlecruisers into carriers; the plan would also expand the Imperial Japanese Navy Air Service and fund the construction of more support and escort vessels.

The Tsurugi-class large cruiser would see a significant increase in firepower, with a uniform five-turret battery of triple 25cm/55 caliber guns—a 50% increase in barrels—improved deck armor and underwater protection, an increased secondary battery of the new 10cm anti-aircraft gun, and even more torpedo launchers. They would more than straddle the line between large cruiser and battlecruiser. They were also better optimized to serve as carrier escorts with their enhanced secondary battery. However, due to the ambitious terms of the Maru 3 plan, the ships would not be laid down until 1937. The class would be thrust directly into the fires of the Pacific War, with Tsurugi and Kurama having their shakedown cruisers while escorting the Kido Butai to Hawaii.

The Japanese would also begin construction of their first class of light cruiser since the completion of the Sendai class in the 1920s. The Aganos were exceptionally light and exceptionally fast, closer to destroyer leaders than true cruisers—which is fitting of their role as destroyer squadron flagships. This would also see the IJN’s oldest light cruisers (both Tenryū cruisers and the first two Kuma cruisers) be temporarily moved into the reserves, though they would be reactivated in 1939 for conversion into either fast troopships (Tenryū and Tatsuta) or torpedo cruisers (Kuma and Tama).

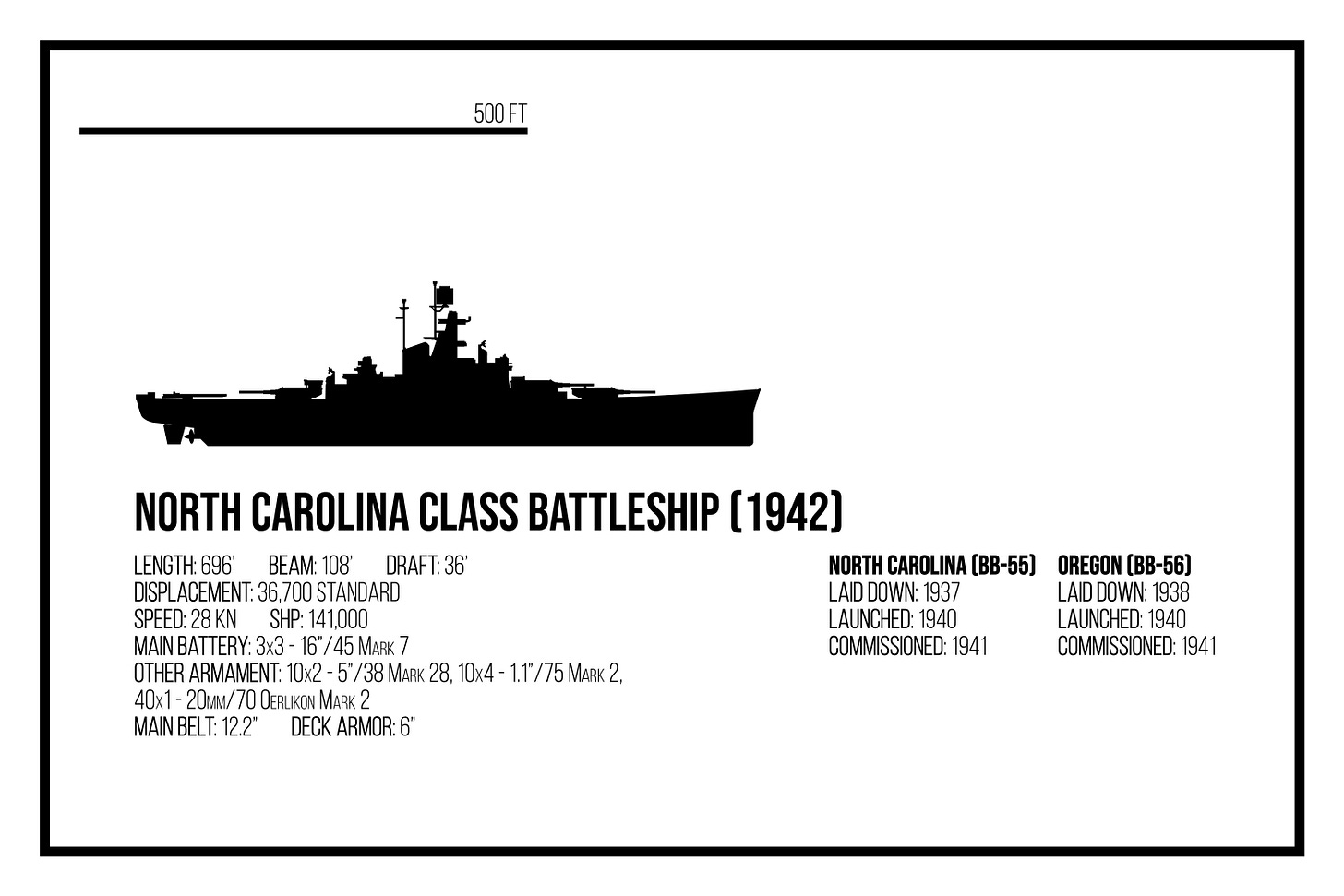

1936 would also see the British and Americans finalize work on their first planned set of treaty battleships. One thing in the interim that became clear was that 35,000 was not sufficient tonnage for a symmetric (protected against its own armament) 16-inch gun-armed battleship.

The British would choose Design 15D—a 35,000-ton design with a 14.5-inch belt and 6-inch deck, nine BL 15”/50 Mk II guns in triple turrets, and a top speed of 28.5 knots. The British would begin construction as soon as the battleship holiday had ended—however, delays caused by industrial bottlenecks would plague the ships.

The United States Navy would nearly select a “Hood type” design with eight 16”/45 guns in four twin turrets. However, it was deemed insufficiently protected. Lessons from the construction of the Ticonderoga-class cruisers and a desire by the General Board for a symmetric ship would see voluminous numbers of iterations between 1934 and 1936.

The final decision was Scheme XXIII, selected in early 1937. The ship would reach 28 knots, barely, with boilers positioned above the turbines and a sharply inclined internal belt (which was only barely accepted). The ship would be armed with nine 16”/45 Mark 7 guns in triple turrets and ten 5”/38 twin mounts. This would all be achieved on a little over 36,000 tons with an overall length of 696 feet.

The Navy, influenced by its experience with the battlecruisers was keenly interested in ensuring the speed of the new ships. The refits of the Concords and the construction of Ticonderogas accelerated the development of more advanced boiler designs and helped maximize the efficiency of the machinery layout of the new designs. There was even a radical and optimistic proposal to use untested centrifugal jet turbines based on the 1930 Whittle patent to provide power for BB-55 and 56, in addition to boilers and geared turbines; however, the plan was considered incredibly impracticable, overly expensive, and was estimated to add at least years to the construction time.

In 1937, the United States, the United Kingdom, and France held another consultation to address a new set of concerns. Italy refused to attend after the Dutch withdrew from their Ansaldo contract and signed their new contract with Vickers-Armstrong but later assented to the proposals. The meeting convened in DC just weeks before the Marco Polo Bridge Incident.

The United States and the United Kingdom were in a bind—they were out of a carrier tonnage while Japan continued to build more flattops. The US was maxed out, while the UK had 7,000 tons but was only interested in building full-sized carriers. The US had come prepared to fight for a contrived argument to retroactively free up 25,000 tons by subtracting 5,000 tons of “refit” tonnage from each of its carriers. The British would just offer to increase carrier displacement by 46,000 tons to permit both nations to procure two more carriers. They, in particular, wanted to build a class of four armored carriers to replace Furious, Courageous, and Glorious (what would become the Illustrious-class carriers). The General Board was also quite relieved when the British flatly shot down President Roosevelt's proposal for a new category of “battle carrier” as a response to Shōhō and Zuihō and intelligence reports that all four Kongo-class battlecruisers were being converted in the mold of Shōhō.

The US Navy was confident that it could match two or three presumed additional battle carriers with a single fleet carrier. There was confusion over how many of the Kongos were to be converted. Haruna and Kirishima were likely. Hiei was considered probable, but Kongo was considered unlikely, with the assumption that she would remain a target ship. The US would order CV-7 shortly after the consultation and lay down the ship in 1937.

There was also the issue of battleship displacement. It was clear to all parties that maximum displacement needed to be increased; the requirements for reasonable deck armor and underwater protection had grown considerably since 1922—effective battle ranges had grown and so had torpedo warheads. The consultation would agree to lift the maximum displacement of battleships to 45,000 tons.

The Italians (retroactively) and the United States would be the only states to take advantage of the larger displacement. The Italian Littorios were already 40,000 tons; the follow-on Giulio Cesares would displace 49,900 tons standard and be the largest warships built in Europe until the French supercarrier Foch in the early 1960s.

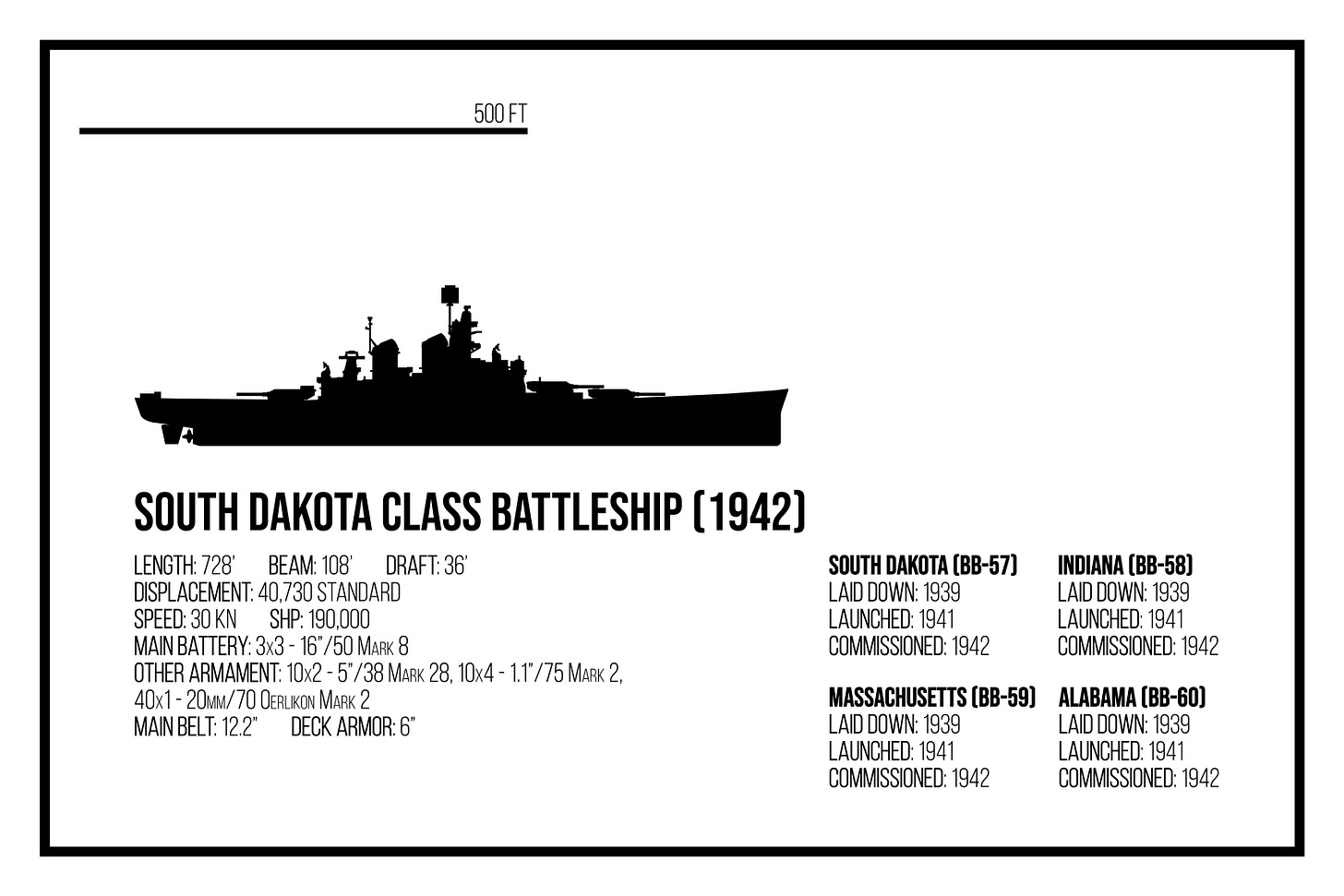

The US Navy would request a 45,000-ton battleship for BB-57, but Congress would only provide the money and tonnage for ships of 40,000 tons per hull. These would become the South Dakota-class battleships.

The class would be armed with nine of the new 16”/50 Mark 8 guns. The Mark 8, a lightened version of the 50-caliber Mark 6 gun, was rapidly designed and built using much of the work completed by the clean-sheet 45-caliber Mark 7 gun used on the North Carolina class. The gun was originally ordered to refit the the Big Three so they could handle the new 2,700 super-heavy Mark 8 shell. Rapid refits from 1939 to 1943 would see the Big Three replace their 5”/25 pedestal mounts and remaining 6”/53 casemates in favor of a uniform secondary battery of twin 5”/38s. The same appropriations that funded these shallow refits would also be used to refit the old Omaha-class cruisers into anti-aircraft ships.

The new Mark 8 gun would be plugged into the still-under-construction South Dakota-class ships. The ships would also be equipped with ten twin 5”/38s mounts and have a maximum speed of 30 knots. Protection would be comparable to that of the North Carolina-class battleships. Most of the additional displacement would go to the extra deck armor and armor belt needed to protect a larger hull.

Continued Japanese super cruiser construction led the US to push for further super cruiser tonnage and an increase in the tonnage limits for the classification. The US wanted 35,000 tons. However, the British would negotiate that down to a ‘mere’ 30,000 tons for what was still a cruiser. The British did not have any interest in further large cruiser production but were perfectly happy to permit the USN to counter Japanese construction.

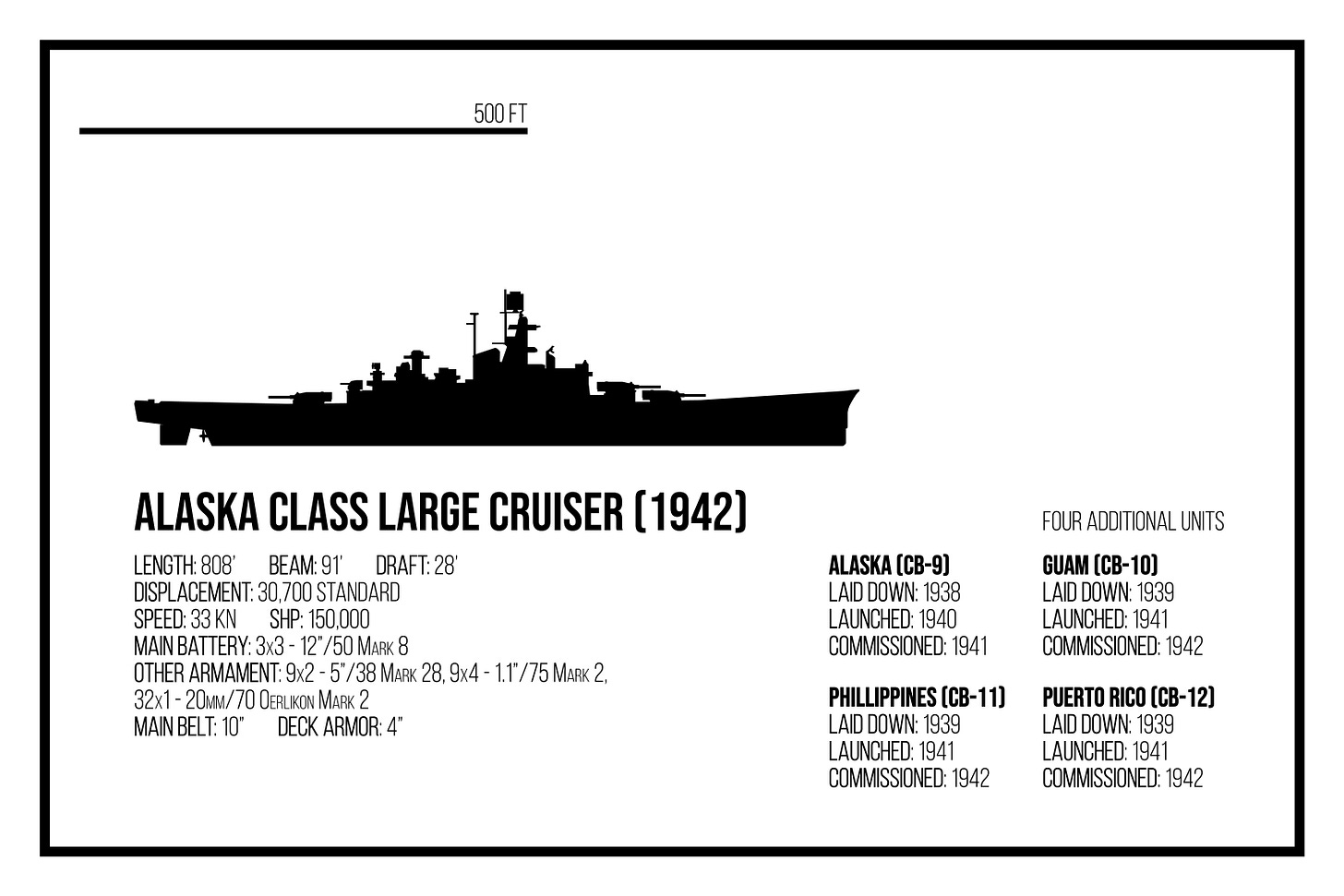

The US would begin construction on the Alaska-class large cruisers, with two in FY38 (Alaska and Guam), two in FY39 (Hawaii and Philippines), three in FY40 (Puerto Rico, Samoa, Virgin Islands), and one in FY41 (Sequoyah). However, only the first four vessels would be completed as large cruisers. The FY1940 ships would be converted into emergency aircraft carriers shortly after being laid down, while Sequoyah would be completed as an experimental “large command and control cruiser” or CBCC to integrate PROMETHEAN and OLYMPIAN-spec technologies to improve CERFOR and GENFOR interoperability.

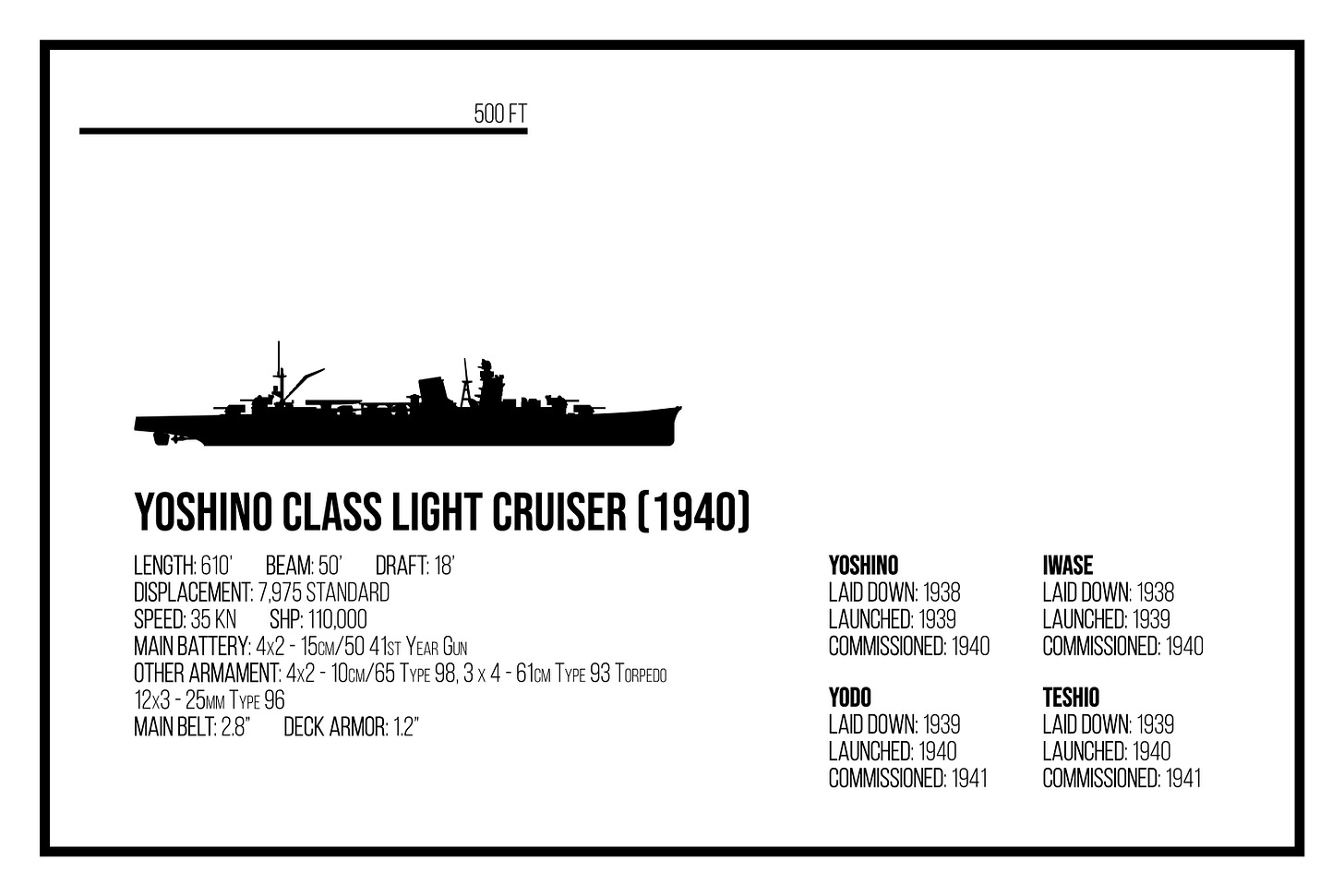

The Japanese Diet would enact a 4th Naval Armament Supplement Programme in 1938, which would fund the final two ships of the Tsuguri-class special type cruisers, two additional Yamato-class battleships, two improved Shōhō-class light carriers, provide additional funding for the Kongo carrier conversions (which had proved more difficult and expensive than hoped), four Type B Yoshino-class light cruisers (improved Agano), and a raft of new destroyers.

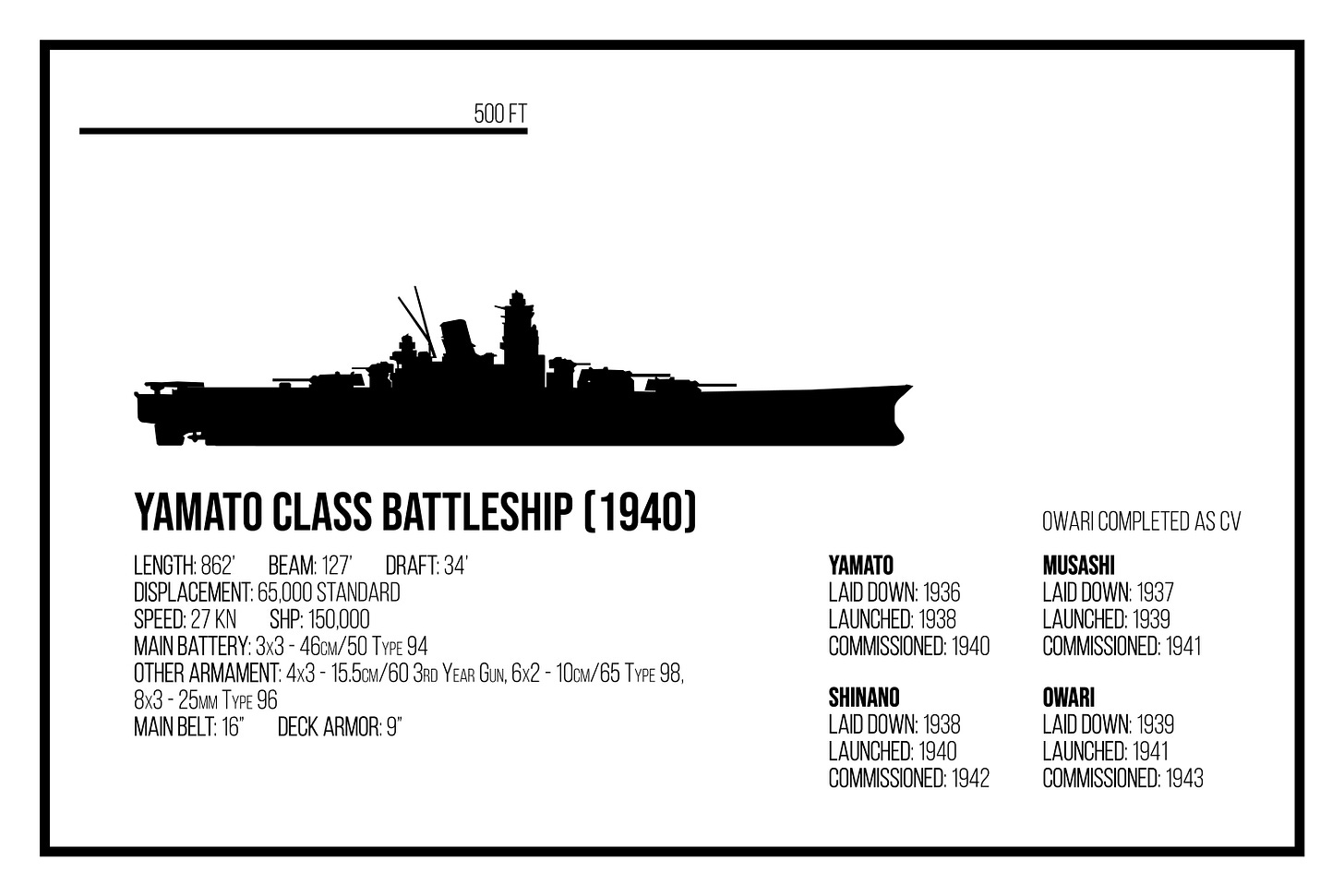

Yamato and Musashi, the giants of the ocean, would be laid down earlier but have an otherwise unaccelerated development and construction (though the ships would be modified on the slipway after the INGS decided to abandon the mixed diesel/turbine powerplant. Shinano would be completed as a battleship in August 1942, and Owari would be substantially modified as Japanese industry strained to keep pace with their huge naval program. Joining her once sistership Kii, she would be converted into a carrier after tense deliberation in early 1942. When she was completed in late 1943, she would be the world’s first completed angled deck carrier.

The Japanese would also order a class of improved Agano-type cruisers to continue replacing their older Great War-style light cruisers. The Yoshinos would see a major increase in armament and armor over the Aganos, with roughly 2,000 tons of extra displacement. These new cruisers would allow the final three ships of the Kuma class to be converted into anti-aircraft cruisers.

Stalin For Time

In June 1933, after much wrangling, the Soviet Union authorizes the reconstruction of the Gangut-class battleship Frunze (originally named Poltava) into a battlecruiser. This work would be stopped no less than three time but would be complete in 1939 after six years. The ship—the Russian Empire’s first generation of dreadnought battleship—could hardly be described as a competitive battlecruiser with only a top speed of 27 knots, but nonetheless, was faster than her less reconstructed sisters. She would be attached to the Black Sea Fleet.

With the appearance of Large Heavy Cruisers on the naval scene, Stalin demands a fleet of large cruisers for the Soviet Union. In 1936 and 1937, several variations were drafted, with Project 25 (which started life as a small battleship) selected as a “large cruiser” despite displacing over 35,000 tons standard—more than a treaty battleship. The class would narrowly avoid being canceled after the purging of several of their designers. They would take form as the Dzerzhinsky class, with the lead ship followed by Lenin, Schors, and Avrora. Dzerzhinsky would be launched by Shipyard No. 200 Communard in Nikoyalev in 1940 and would be outfitting when the Nazis invaded in 1941. She would be missing some fittings and would only be commissioned in 1942. Lenin would be launched by Shipyard No. 1941 Marti in Leningrad and launched in late 1940; and never formally commissioned during the war but would be used in the defense of Leningrad. Schors would be launched in 1941 thanks to her shipwrights having cut their teeth reconstructing Frunze; she would be launched ahead of the Nazi advance on Nikoyalev and be used as an important high-speed troopship during the Black Sea campaign. Avrora would be roughly 40% complete when Nazi closed in on Leningrad, and much of the material gathered for her construction would be diverted to help build defensive works around the city.

Stalin would then order the construction of no less than 15 large battleships as a part of the 1938 Naval Works Programme. The ships, Sovetsky Soyuz class, would barely have begun work when the invasion of the soviet union began. However, due with the experience of more large ship production would lead to an accelerated schedule for the Chapayev-class light cruisers, Kiev-class destroyer leader, and Ognevoy-class destroyers. Notably, the cruisers Kuybyshev, Zhdanov, Ordzhinikidze, and Parkhomenko, plus the destroyer leaders Kiev and Erevan and destroyers Ognevoy, Ozornoy, and Otverzhdyonny would be 1938 Programme ships that would make the “Mad Run” of the Black Sea Fleet to Alexandria in August of 1942.

Panic! At the General Board

The War in Europe begins in September 1939 and kills the Treaty System.

USS Hornet (CV-8) is laid down that same month.

1940 is no better. In fact, the events of that year shake the United States to its very foundations. France, the greatest land power in Europe, had withstood four years of brutal fighting in the First World War. It is a sister republic to the United States. It collapses in just six weeks—against all expectations.

In the following weeks, Congress authorizes a 70% increase in the Navy’s displacement with the Two Ocean Navy Act. Franklin Roosevelt is nominated for an unprecedented third term as President. Then, to wrap, Congress enacts a peacetime draft for the first time in American history.

Then, another revelation—the Kongo-class battlecruisers had not been converted into fool-hardy, half-ass battle carriers; they had been converted into fleet carriers. US intelligence had originally assessed that only Kirishima, Hiei, and Haruna would be converted while Kongo would remain a target ship. But, much like how US intelligence assessed that the Nagato and Tosa class battleships were only capable of 23 knots for over a decade, this was not accurate. To make matters even worse, the same reports that had confirmed the nature of the Kongo class conversion program had spotted that the scout carriers Shōhō and Zuihō had been spotted in the middle of a work to extend their flight decks.

In 1940, the United States has six fleet carriers in service—Lexington, Saratoga, Ranger, Yorktown, Enterprise, and Wasp with one fleet carrier under construction, Hornet.

Japan also has six fleet carriers in service at this point—Akagi, Kii, Soryū, Hiryū, Zuikaku, and Haruna; but four more under construction—Shōkaku and Hiei were outfitting, Kirishima and Kongo were still undergoing reconstruction (the latter was proving particularly troublesome). While the IJN only has two light carriers in active service—Hōshō and Ryūjō (both of questionable value in 1940), they have two more under construction; Shōhō and Zuihō had returned to the yard to be converted into flush-deck carriers.